Collection 24

The one-year provenance research project sponsored by the BAK intensively analysed a total of 54 works from the Aargauischer Kunstverein.

The Häuptli Collection was particularly suitable for in-depth research for two reasons: firstly, because of its artistic significance for the Kunsthaus, and secondly, because of the provenance information already available. Fifty works were selected from the collection for in-depth provenance research. The Aarau couple Valerie and Dr. Othmar Häuptli collected modern art for two decades – between around 1930 and 1950. They did not follow a strict collection profile but bought what they liked.

The resulting collection of 105 works, mainly paintings, was donated to the Aargau Art Association by the couple in 1970. Othmar Häuptli died in 1983, and the collection came to the Aargauer Kunsthaus in accordance with his will.

Unfortunately, there is little concrete information on the history of the collection, as the Häuptlis not only collected exclusively according to their taste, but also remained reserved as buyers and did not appear in public very often. They bought in the national and international art trade – mostly in (southern) Germany. The couple acquired most of their works from the galleries Aktuaryus (Zurich), Fischer (Lucerne), Griebert (Munich/Constance), Ketterer (Stuttgart), Rosengart (Lucerne) and presumably Nierendorf (New York). Roman Norbert Ketterer and Häuptli were personally acquainted. Ketterer had apparently visited the couple in Aarau. Othmar Häuptli also acquired several works of art from the Glarus collector and fellow doctor Othmar Huber, like when he financed his daughter’s trousseau in the early 1950s. The two collectors were friendly rivals.

Valerie and Othmar Häuptli were also personally acquainted with a number of artists: Erich Heckel and his wife Siddi, for example, visited the Häuptlis in Aarau in spring of 1965 and were in friendly correspondence with each other.

The provenance research project focused on several categories of works. Firstly, works by artists who were considered ‘degenerate’ under National Socialism were analysed in more detail. The following artists are represented in the Häuptli Collection: Ernst Barlach, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, August Macke, Otto Mueller, Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. These works actually form the centrepiece of the collection.

In addition, works by French artists such as Paul Cézanne, Camille Corot, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Auguste Rodin and Georges Rouault were analysed more closely. With these works, it was particularly important to investigate whether they were confiscated objects from occupied France (1940-1944).

In addition, works by Ferdinand Hodler and Cuno Amiet were also researched in more detail, as they were well represented in the international (German) art trade during the first half of the 20th century.

In addition to the Häuptli Collection, three watercolours by Paul Klee and a painting by Ferdinand Hodler from another donation to the Aargau Art Association were included in the project because there were already a number of references to these works and their provenance chains were almost complete.

The one-year provenance research project has therefore intensively analysed a total of 54 works from the Aargau Art Association.

(Text by Caroline Lange)

Case studies

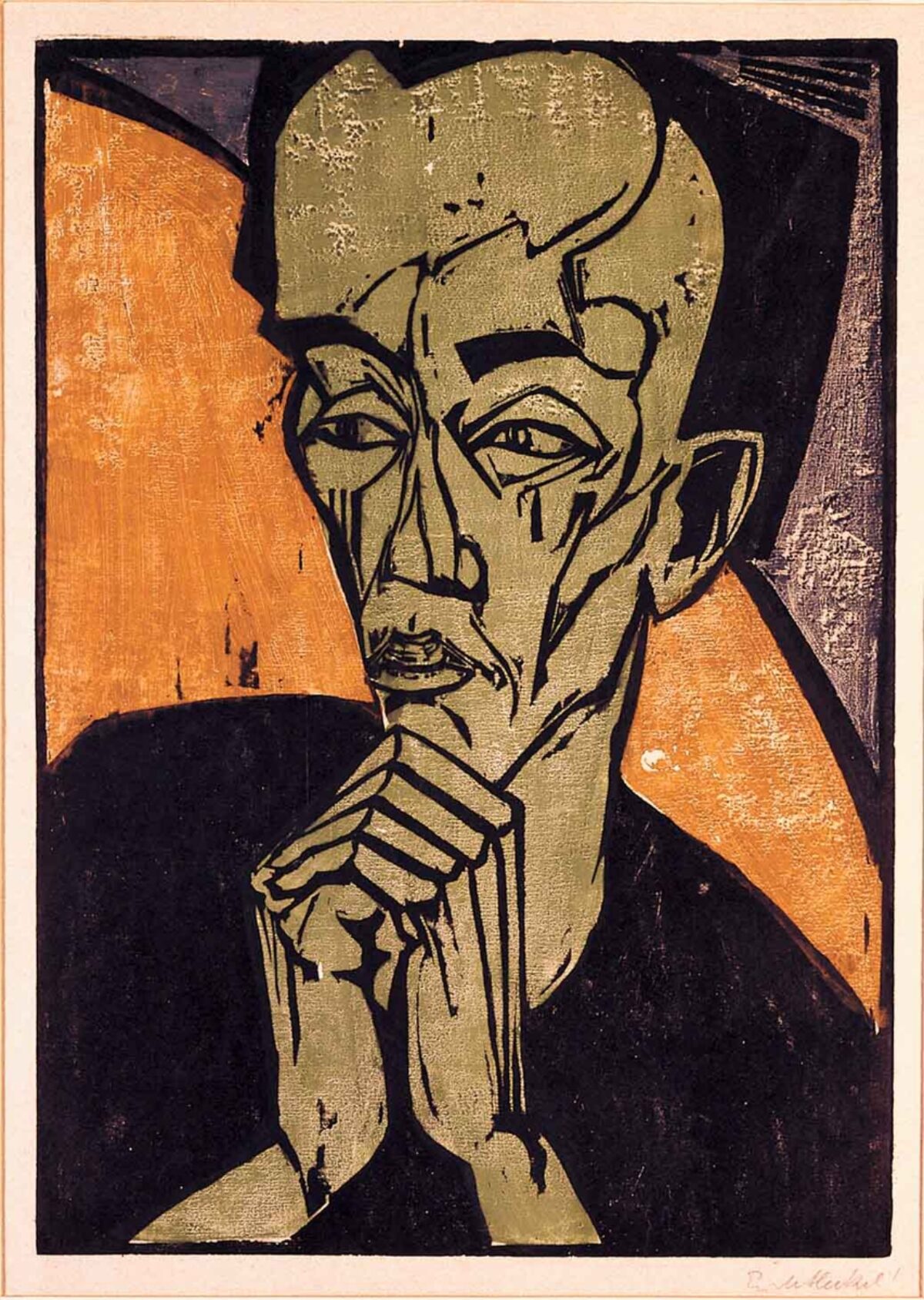

Erich Heckel, Männerbildnis (Portrait of a man), 1919

The woodcut was a gift from the artist to Othmar and Valerie Häuptli, which he delivered personally during a visit to Aarau in the spring of 1965.

On 15 January 1965, Valerie Häuptli wrote to the “esteemed Master Heckel” and told him about a watercolour portrait that had been hanging in her husband’s office in the surgical clinic in Aarau for years. At the request of Siddi Heckel, the artist’s wife, the Häuptlis had a print made and sent so that it could be used for the catalogue raisonné: “We thought you would certainly be pleased to have it as a photograph again.” At the end of her letter, Valerie Häuptli invites the Heckel couple – if “your health permits” – to come to Aarau. They would be delighted “if you were to pay us and our small collection a visit.” [1]

It seems Siddi Heckel replied immediately to this letter and agreed to a visit – an undated draft of this letter survived [2] – and only a week later, on 22 January 1965, Valerie Häuptli wrote: “We thank you very much for your kind letter and would like to express our pleasure at having you with us. We are reserving the afternoon of Saturday, 13 February 1965 for your visit.” The two of them would be received at “13.21 on platform 2, and then we will sit and enjoy a nice cup of coffee before we look at the “Brücke” paintings.” [3]

The visit apparently took place as planned, and on 2 March 1965, Othmar Häuptli wrote to the Heckels to thank them for two gifts they had brought him and his wife. One of the gifts was a copy of Oscar Wilde’s “Ballad of the Penitentiary at Reading”, published in 1898 – the last work published during Wilde’s lifetime. The second gift was woodcuts, one of which is now in the Othmar and Valerie Häuptli Collection at the Aargauer Kunsthaus. Whether there were two or possibly more woodcuts cannot be ascertained from the correspondence. “We are delighted with this precious gift and thank you very much for it.” The Oscar Wilde ballad seems to have been given in its English version, but Othmar Häuptli was confident that he would “tackle the text at some point”. [4] He had more to say about the woodcut (1919, 61.3 x 44 cm), which today bears the signature G3022 and the title Männerbildnis (Portrait of a Man) in the collection: “Your woodcuts captivate us with their abstract design and their strong statement. These woodcuts show us again that abstract art must have a relationship to the figurative. […] If the viewer is to have a relationship to the masterpiece, the work must convey a thought to him […]. That is how it comes alive for him. […] And your woodcuts speak in a lively language.” This correspondence between the Häuptlis and Erich Heckel not only clarified the provenance of the woodcut, but also gives us an interesting insight into the relationship and interaction between collector and artist and into the private reception of art.

(Text by Caroline Lange)

Footnotes

[1] Valerie Häuptli to Erich Heckel on 15 January 1965, Erich Heckel Estate / Erich Heckel Foundation.

[2] Draft reply from Siddi Heckel to Othmar and Valerie Häuptli, after 15 January 1965, Erich Heckel Estate / Erich Heckel Foundation.

[3] Valerie Häuptli to Erich Heckel on 22 January 1965, Erich Heckel Estate / Erich Heckel Foundation.

[4] Othmar Häuptli to Erich Heckel on 2 March 1965, Erich Heckel Estate / Erich Heckel Foundation.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Der Wanderer (The Wanderer), 1922

Das Bild Der Wanderer von Ernst Ludwig Kirchner entstand 1922, als der Künstler sich infolge seiner Krankheit in Davos aufhielt. Bereits im gleichen Jahr wurde das Gemälde von Heinrich Staub (1866–1962) gekauft. Kirchner hatte offenbar nicht erwartet, dass sich überhaupt jemand für das Sujet interessieren und er das Gemälde in so kurzer Zeit verkaufen würde. Am 22. Dezember 1922 schrieb er der Künstlerin Nele van de Velde: «Ich male jetzt fast nur so, kaum mehr von der Natur. So habe ich den Wanderer gemalt, weite Berglandschaft, gerade Strasse zwischen Ödland. Darauf der Mann gebeugt gehend. Das Bild gehört dem Dr. S. auf Clavadel. Ich staunte sehr, dass so etwas gekauft wurde. Ich kämpfe um grosse ruhige Flächen und tiefe volle Farben. Ich will mehr geben als nur Seherlebnisse.» [1]

Aus einem anderen Brief Kirchners an seinen Freund und Mäzen in Frankfurt a.M. Carl Hagemann erfahren wir mehr über die Rezeption des Bildes: «Der Mann, der mein Bild Wanderer kaufte, tat das, weil ihm der seelische Gehalt des Bildes so sehr einging.» [2]

Kirchner lernte Heinrich Staub und seine Frau Julia Staub-Oetiker – «ganz reizende Leute, für Kunst interessiert» [3] – im Jahr 1921 in Davos kennen. Die beiden Ärzte arbeiteten zu diesem Zeitpunkt in der Klinik in Davos-Clavadel, wo sie auch kulturelle Veranstaltungen förderten.

Der Wanderer gelangte später in die Sammlung eines anderen Arztes, Othmar Häuptli, der das Bild nachweislich von Heinrich Staub erwarb und wie sein Arztkollege grosse Begeisterung für die Kunst des Expressionismus zeigte.

(Text von Nora Togni)

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s painting The Wanderer was created in 1922, when the artist was staying in Davos due to his illness. The painting was purchased by Heinrich Staub (1866-1962) in the same year. Kirchner had obviously not expected that anyone would be interested in the subject at all nor that he would sell the painting in such a short time. On 22 December 1922, he wrote to the artist Nele van de Velde: “I now almost exclusively paint like this, not much from nature anymore. This is how I painted The Wanderer, a wide mountain landscape, a straight road through wasteland. The man is walking on it, bent over. The painting belongs to Dr. S. in Clavadel. I was amazed that something like this was bought. I strive for large, calm surfaces and deep, full colours. I want to give more than just visual experiences.” [1]

In another letter from Kirchner to his friend and patron in Frankfurt am Main, Carl Hagemann, we learn more about the reception of the painting: “The man who bought my painting The Wanderer did so because he was so impressed by the emotional content of the painting.” [2]

Kirchner met Heinrich Staub and his wife Julia Staub-Oetiker – “very charming people, interested in art” [3] – in Davos in 1921. At the time, the two doctors were working at the clinic in Davos-Clavadel, where they also sponsored cultural events.

The Wanderer later found its way into the collection of another doctor, Othmar Häuptli, who demonstrably acquired the painting from Heinrich Staub and, like his doctor colleague, showed great enthusiasm for Expressionist art.

(Text by Nora Togni)

Footnotes

[1] Letter from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner to Nele van de Velde dated 22 December 1922, in: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Briefe an Nele und Henry van de Velde, Munich: R. Piper & Co. publishing house, 1961, p. 47.

[2] Letter from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner to Carl Hagemann dated 19.11.1935, in: Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Nolde, Nay… Briefe an den Sammler und Mäzen Carl Hagemann 1906-1940, ed. and annotated by Hans Delfs et al., Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2004, p. 502.

[3] Letter from Ernst Ludwig Kirchner to Nele van de Velde dated 7 October 1921, in: Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Briefe an Nele und Henry van de Velde, München: R. Piper & Co. Verlag, 1961, p. 44; see also:

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Der gesamte Briefwechsel, Vol. I, Briefe von 1901-1923, ed. and annotated by Hans Delfs, Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2010, pp. 507-508.

The Aargauer Kunsthaus would like to thank the Federal Office of Culture and Swisslos Canton Aargau for their financial support.

The Aargauer Kunsthaus is working in collaboration with Lange & Schmutz Provenienzrecherchen GmbH on the provenance research project.