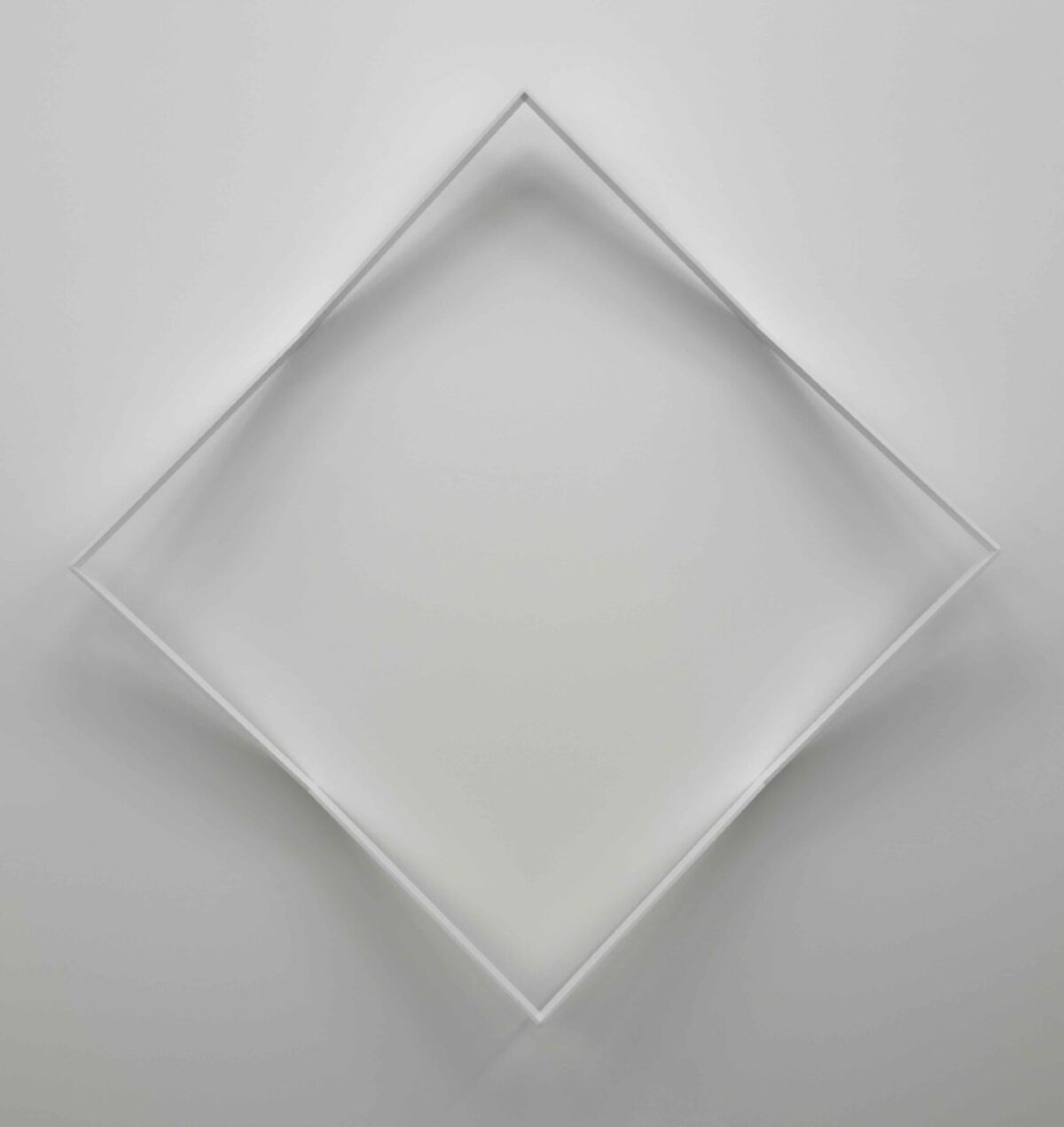

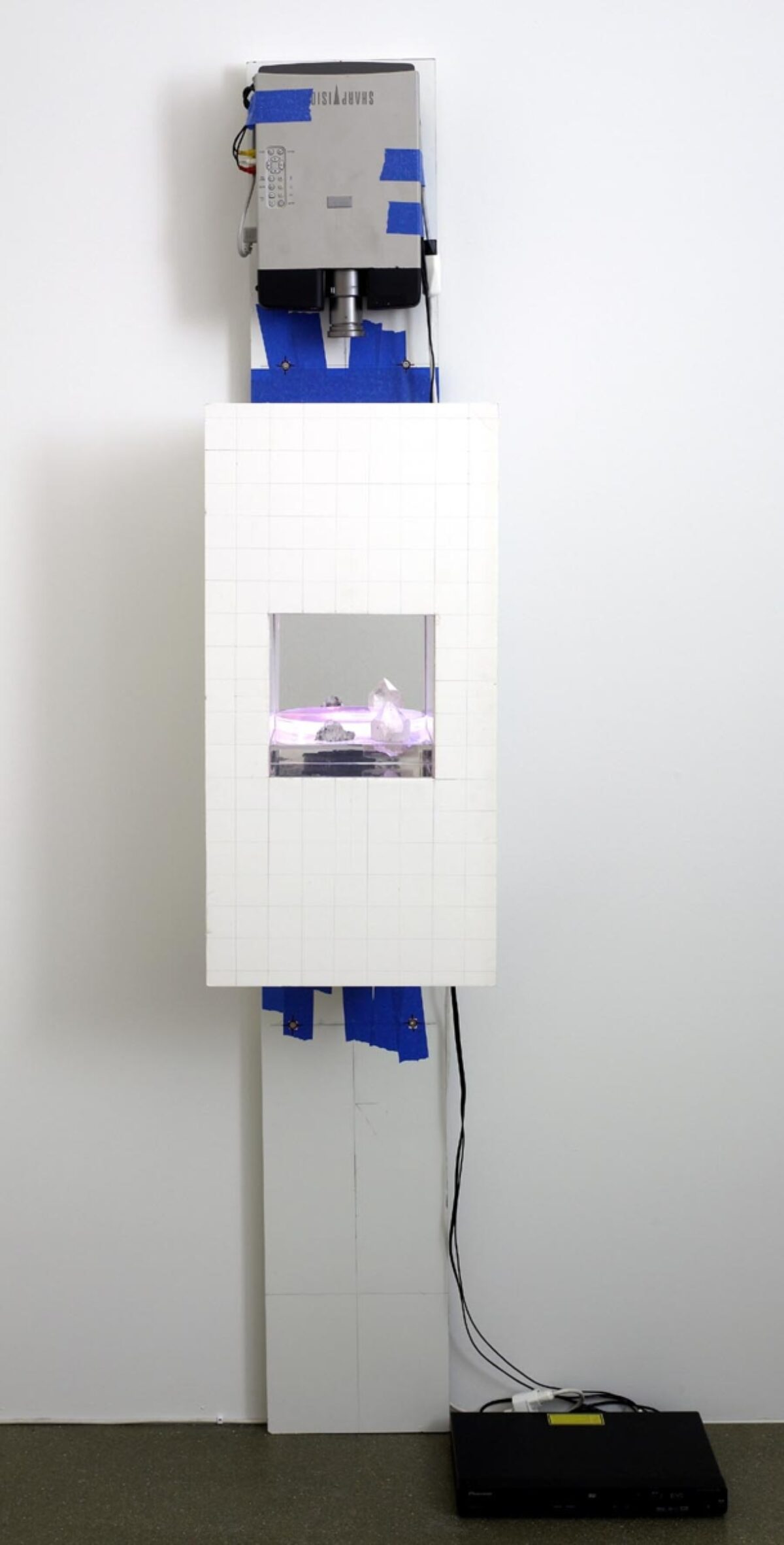

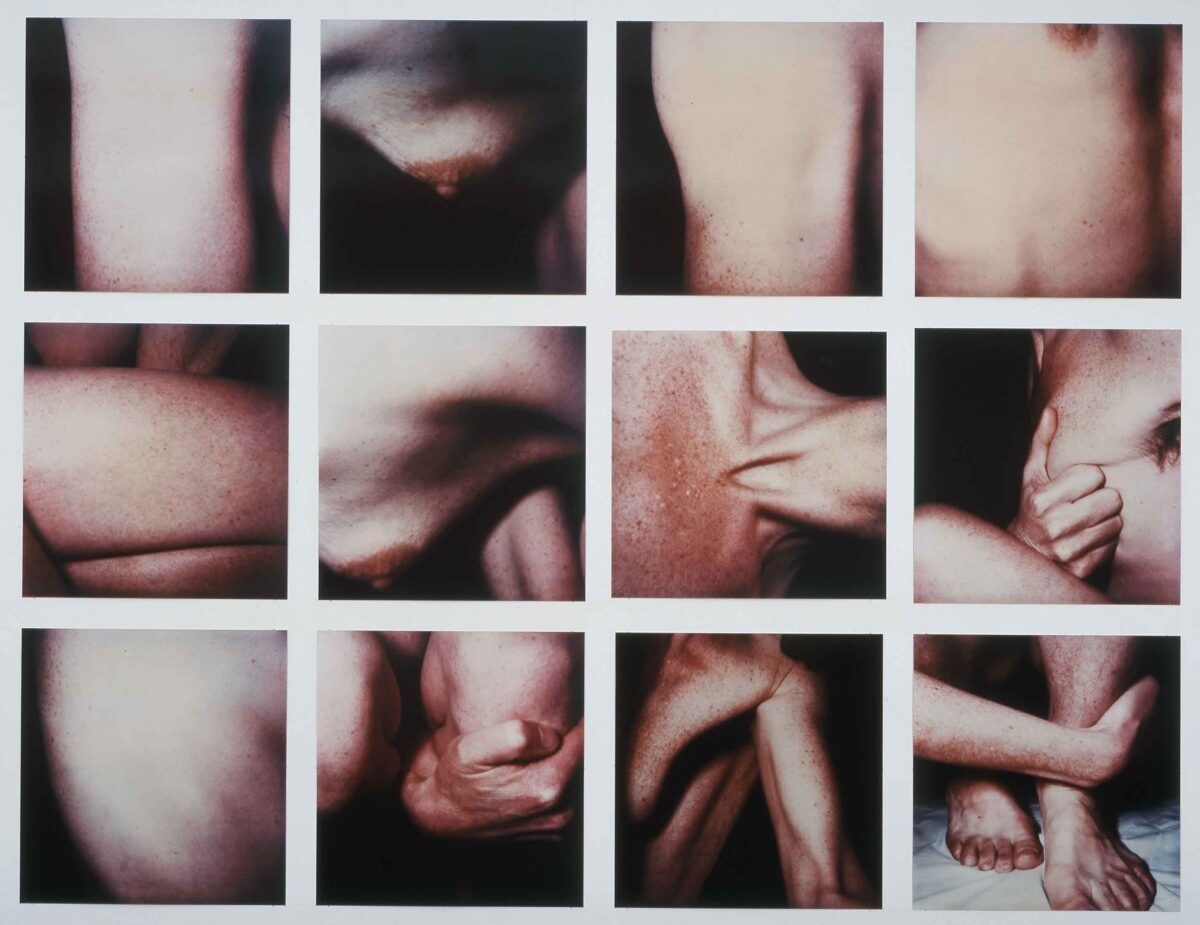

C-Print ab Polaroidvorlage auf Aluminium (12-teilig), 348 x 464 cm

English, french and italian version below

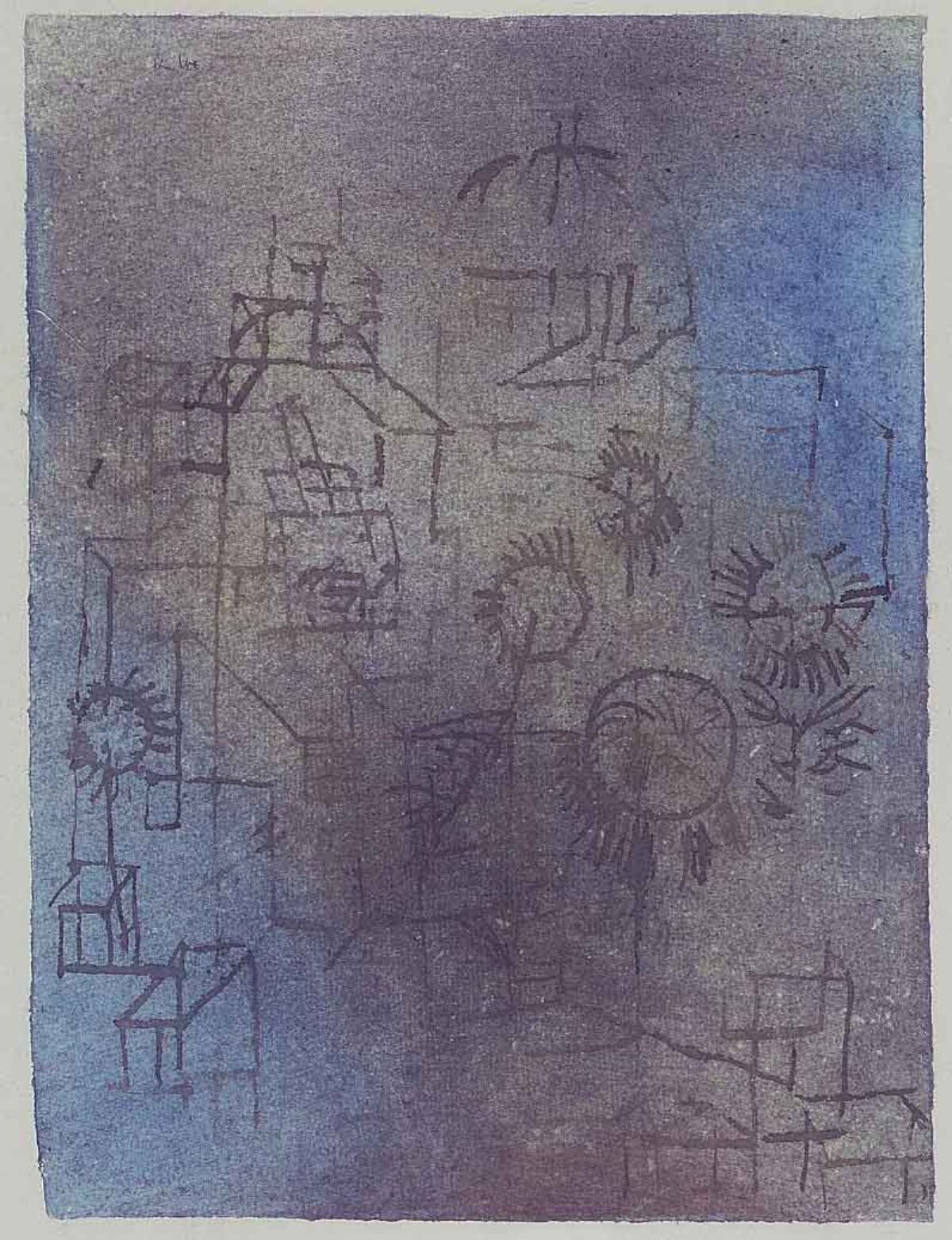

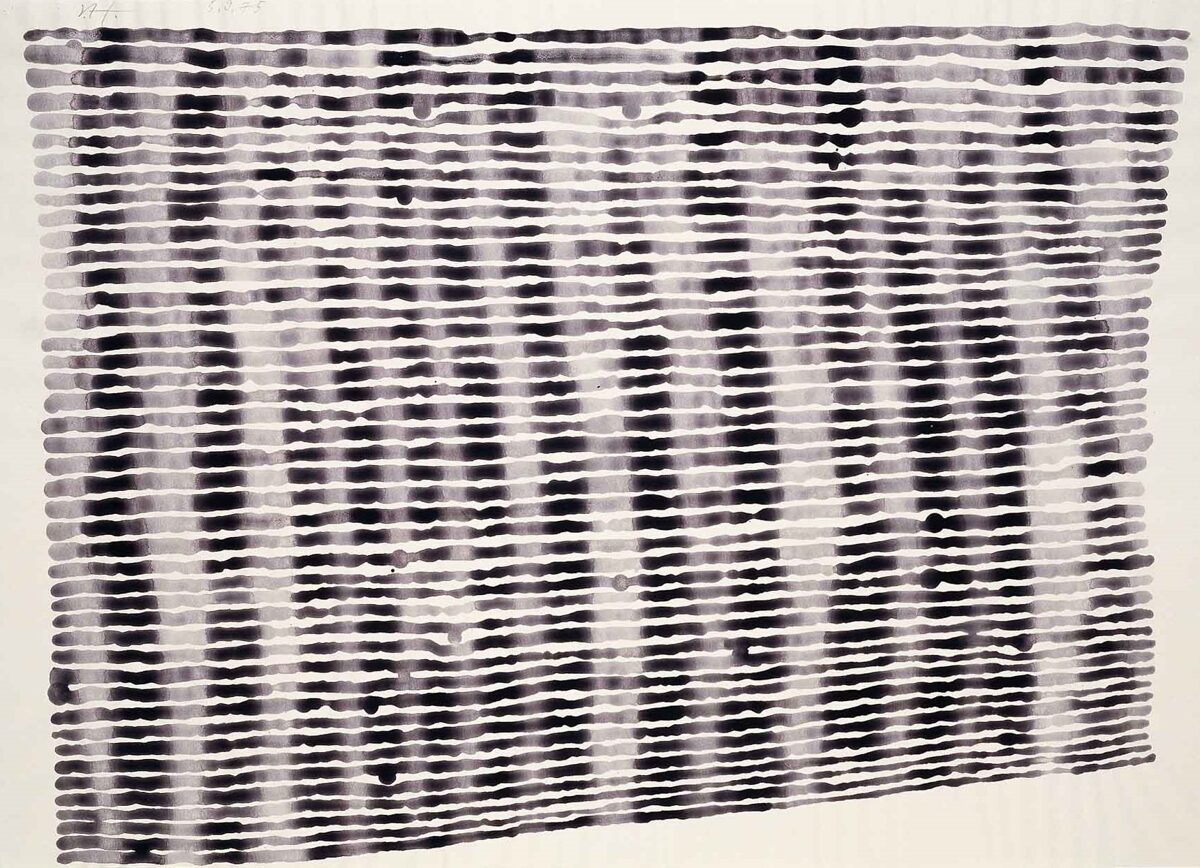

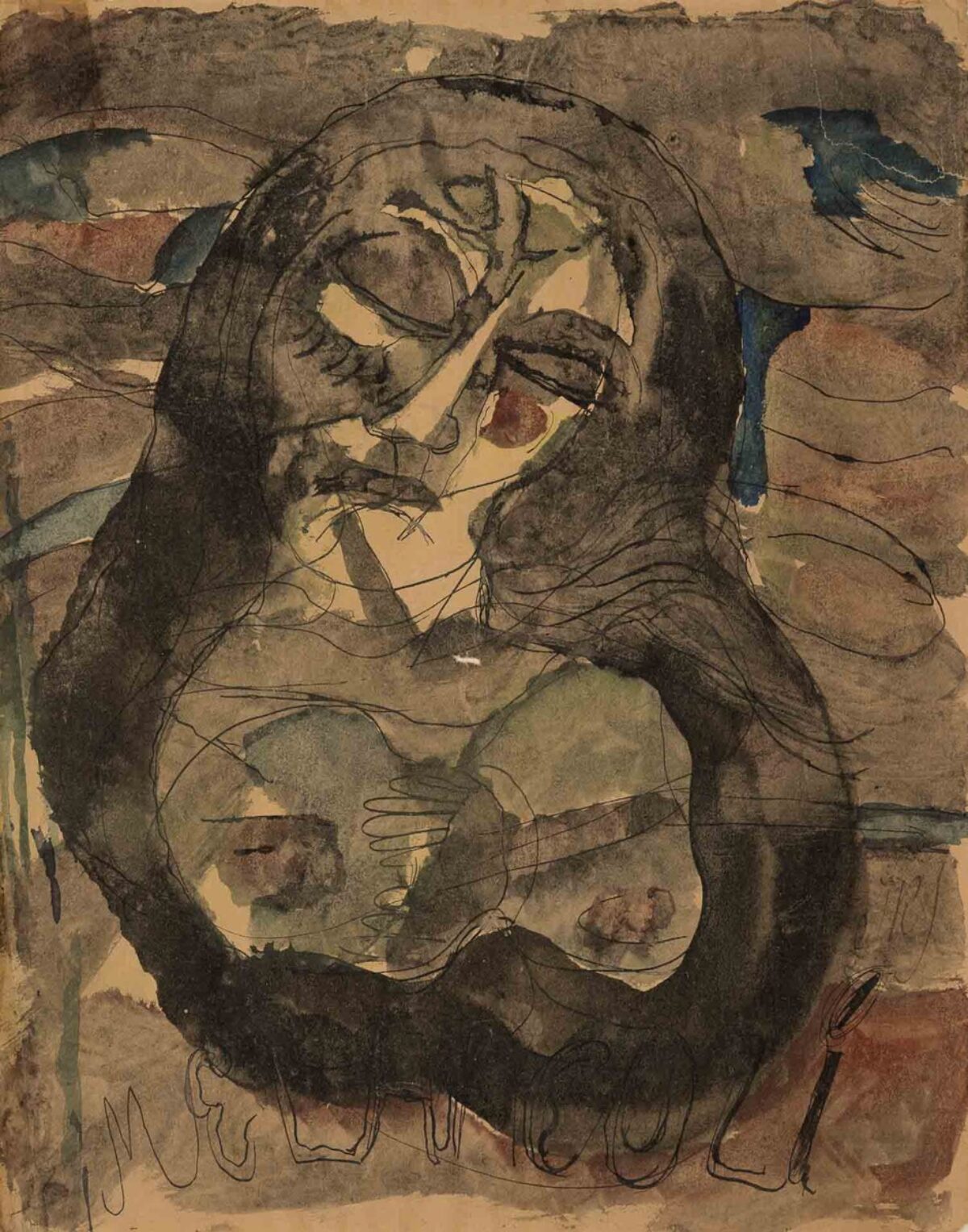

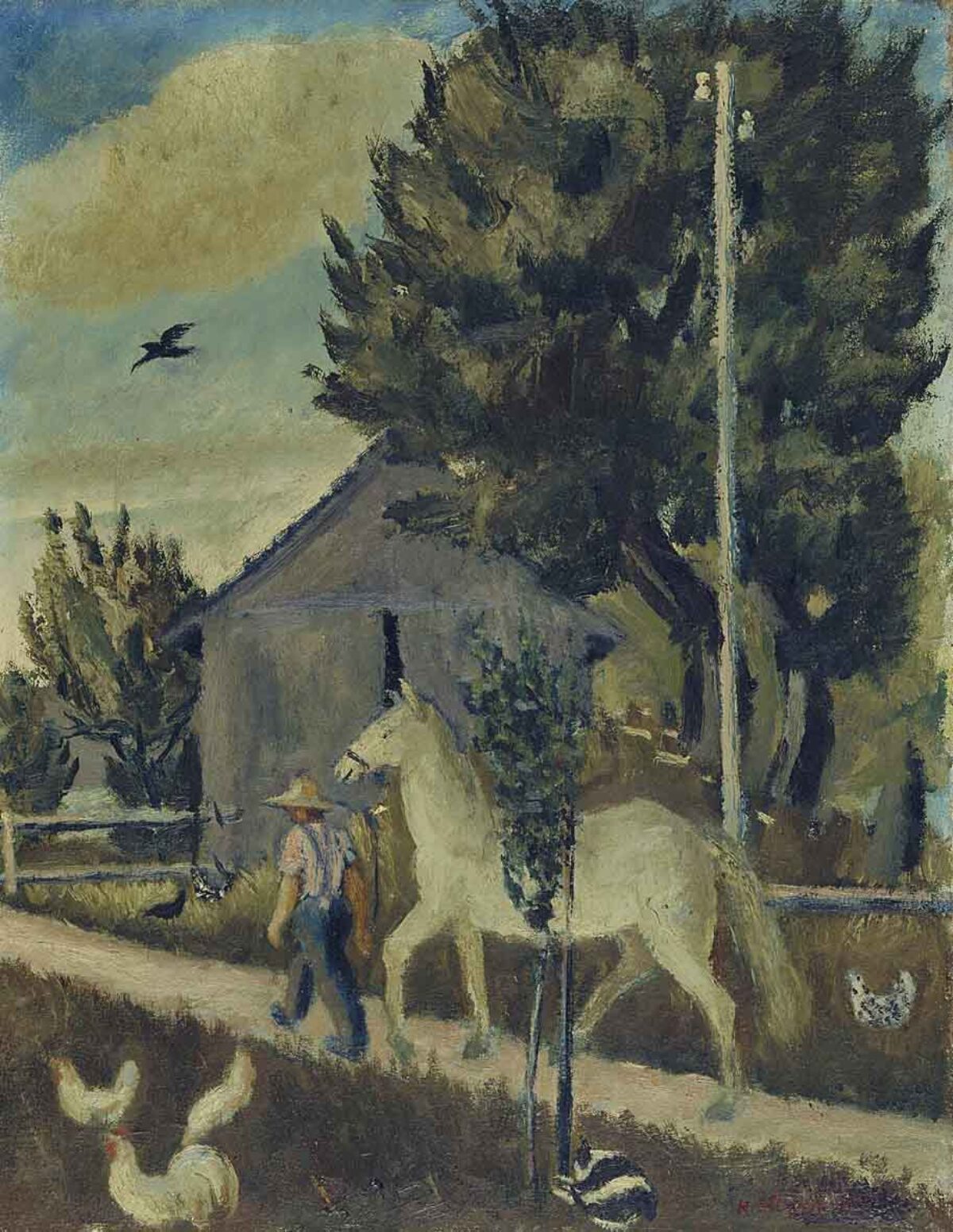

Mit „Block I“, der ersten allein aus Teilansichten des eigenen Körpers gebildeten Fotowand von Hannah Villiger (1951–1997), bewahrt das Aargauer Kunsthaus eines der wichtigsten Schlüsselwerke der Künstlerin auf. Die Arbeit ist 1988 entstanden, doch die darin vermittelte Idee von Weiblichkeit, welche die Haut und die Gliedmassen als Material einer autonomen skulpturalen Erkundung begreift, wurzelt letztlich bereits im Frühwerk. In kleinen Objekten und Installationen nimmt Villiger damals Impulse der Arte Povera auf und gibt ihnen einen feministischen Dreh. So beinhalten etwa die Speer- und Lanzettformen aus pflanzlichem Material, die sie 1975 an der Biennale des Jeunes in Paris und ein Jahr später im Tessin an der G’76 in Vira Gambarogno zeigt, eine explizit genderspezifische Note. Auch Momente der Aggression und Gefährdung klingen in diesen Arbeiten an – Aspekte, die im Abschälen von Ästen und Stämmen schon 1974 aufscheinen und zugleich den nackten Körper vorformulieren, der sich roh und verletzlich zeigt.

Wie die Beispiele belegen, präsentiert sich Villiger anfangs als Plastikerin. Nach dem Grundsatz „ich mit dem Objekt“ behält sie dieses Selbstverständnis auch bei, als die Fotografie zum stets zentraleren und schliesslich alleinigen Instrument ihrer künstlerischen Befragung wird. Diese Ausschliesslichkeit ist 1980 erreicht, als Villiger aufhört, ihre Kleinbildkamera auf flüchtige, oft ferne Motive zu richten. Stattdessen greift sie nun meist zur Polaroidkamera, mit der sie aus einem engen Radius heraus agiert. In der Folge entstehen zum einen Serien, die den Blick vom jeweiligen Wohn- oder Atelierraum auf die nächste Umgebung dokumentieren. Zum andern beginnt die intensive Beschäftigung mit dem eigenen Körper, die – wie die Body Art – mit der Wahl des Mediums auch nach einer zeitgemässen Form der Darstellung fragt. Schon 1980 konsolidiert sich diese Praxis anlässlich der Ausstellung „4.1“ im Aargauer Kunsthaus in ersten, mithilfe von Internegativen gross abgezogenen C-Prints. Das kleine, private Sofortbild wird damit zum konfrontativen Manifest. 1983, als der unbekleidete Körper in den Fokus rückt, wird das Mass noch einmal auf den neuen Standard von 125 x 123 cm erweitert und nur noch selten – wie hier, wo der Block durch etwas kleinere Tafeln von 105 x 108 cm austariert wird – unterschritten. Zudem weicht der bisherige Einheitstitel „Arbeit“ der fortan für alle einzeln gezeigten Blow-ups von Körpermotiven gültigen Bezeichnung „Skulptural“.

In der Intimität ihres Ateliers hält Villiger nun sich selbst respektive Teile ihres Körpers mit ihrer SX70 immer wieder bildfüllend fest: mal hautnah, mal soweit es der ausgestreckte Arm ihr erlaubt. Ihr Beharren auf dem eigenhändigen Drücken des Auslösers begünstigt, dass die vertraute Syntax der Glieder – teils unter Einbezug von Spiegeln – in der Nahsicht zerfällt. Gänzlich frei von narzisstischer Selbstverliebtheit hintertreibt Hannah Villiger so die Konventionen des Schönen und Aufreizenden: Der weibliche Akt, den der männliche, latent oder offen voyeuristische Blick über Jahrhunderte hervorgebracht hat, erfährt in der fragmentierten Wiedergabe seine Zerlegung. An seine Stelle tritt ein Körperbild, das zwar vom eigenen, subjektiven Dasein ausgeht, letztlich aber zum anonymen Körper wird, zu einem Körper per se, dessen Wahrnehmung sich aktiv steuern oder, so Villiger, im Dialog mit sich selbst gleichsam bildhauerisch formen lässt.

Villigers Selbstbeobachtung, die 1980 im Jahr der Erkrankung an offener Tuberkulose einsetzt, durchläuft dabei eine deutliche Wandlung. Sind die Arbeiten anfangs noch von erotischem Begehren und Metaphern schwankender Gefühlslagen bestimmt, so gewinnt die tastende, den Körper nahezu topografisch erfassende Sicht rasch immer mehr Raum. Momente gläserner Auflösung alternieren nun mit einer entwaffnend direkten Selbstvergewisserung, die auch aus manchen der eingenommenen Posen spricht. Dagegen erweist sich der Umgang mit den Bildausschnitten als durchwegs instabil. Mitunter wird die Desorganisation des Körpers sogar so weit vorangetrieben, dass eine kaum mehr zu entschlüsselnde Mehrdeutigkeit resultiert. In der Blockhängung, wie sie die Künstlerin 1981 erstmals vornimmt und ab 1988, beginnend mit dem vorliegenden Werk, auch im Titel benennt, finden die losen Enden dann neu zusammen: „[…] hohe Präsenz; Vervielfachung; es muss ein Ganzes sein, und jeder Teil muss eigenständig funktionieren.“

Astrid Näff, 2021

***

With “Block I”, the first photo wall by Hannah Villiger (1951–1997) consisting solely of partial views of her own body, the Aargauer Kunsthaus holds one of the artist’s key works. It is a piece from 1988, but the notion of femininity it conveys in using skin and limbs as material for an autonomous sculptural exploration ultimately has its roots already in the early work. At the time, Villiger drew on the influence of Arte Povera and gave it a feminist twist in small-scale objects and installations. The spear and lancet shapes made of plant material, for example, which the artist showed at the 1975 Biennale des Jeunes in Paris and a year later in Ticino at the G’76 in Vira Gambarogno, have an explicitly gender-specific element to them. Even some hints of aggression and endangerment can be discerned in these works – aspects which became evident as early as 1974 in the debarking of tree branches and trunks and at the same time prefigured the naked body, which appears raw and vulnerable.

As the examples show, Villiger initially presented herself as a sculptor. Based on the principle of “I with the object”, she maintained this self-image even when photography became an ever more central and, ultimately, the sole instrument of her artistic inquiry. It achieved this exclusive status in 1980 when Villiger stopped directing her 35mm camera at fleeting and often distant subjects. Instead, she now tended to resort to the Polaroid camera, which she operated from a tight radius. Subsequently, she created series documenting the view of the immediate surroundings from the particular living or studio space. At the same time, she embarked on an intensive examination of her own body, work which, like Body Art, calls for a contemporary form of representation along with the choice of medium. This practice became consolidated as early as 1980 in first large-scale C-prints created by means of internegatives, which were shown in the “4.1” exhibition at the Aargauer Kunsthaus. The small-scale, private instant picture thus became a confrontational manifesto. In 1983, when the artist started focusing on the naked body, the picture size was again enlarged, with the new – and rarely not met – standard size being 125 x 123 cm, as in this case where the “Block” is balanced out by slightly smaller panels measuring 105 x 108 cm. At the same time, the previous uniform title, “work”, made way for the term “sculptural”, which went on to be applied to all individually presented blow-ups of body images.

In the intimacy of her studio, Villiger now consistently captured herself or parts of her body with her SX70 in frame-filling photographs: sometimes up close, sometimes as far as her outstretched arm allowed. She insisted on pressing the shutter release herself, which is one reason why the familiar syntax of the limbs – sometimes involving mirrors – disintegrates in close-up view. Completely free of narcissistic self-love, Hannah Villiger thwarts the conventions of beauty and seduction: the female nude, created over the centuries by the male, covertly or openly voyeuristic gaze, is broken down in the fragmented rendering. It is replaced by an image of the body which starts out from the individual, subjective existence, but ultimately becomes an anonymous body, a body per se whose perception can be actively controlled or, as Villiger puts it, sculpturally modelled in dialogue with oneself.

Villiger’s self-observation, which began in 1980, the year she was diagnosed with open tuberculosis, underwent significant change in the process. While at first the works were informed by erotic desire and metaphors of fluctuating emotional states, the tentative, almost topographically scanning view quickly gained importance. Moments of transparent dissolution now alternated with a disarmingly direct self-reassurance, which also shows in some of the poses struck. In contrast, the approach to image details proved to be consistently unstable. Sometimes the disorganisation of the body was even pushed to the point where it took on an almost indecipherable ambiguity. In the block-like hanging of the photographs, which the artist first deployed in 1981 and started referring to in her titles in 1988, beginning with the work discussed here, the various loose ends then came together in a new way: “… strong presence; multiplication; it has to be a whole, and each part has to function independently.”

Astrid Näff

***

Avec «Block I», le premier mur de photos de Hannah Villiger composé uniquement de vues partielles de son propre corps, l’Aargauer Kunsthaus conserve une des plus importantes œuvres clés de l’artiste. L’ouvrage a été réalisé en 1988, mais l’idée de féminité qu’il véhicule et qui conçoit la peau et les membres comme matière à une exploration sculpturale autonome prend, en fin de compte, déjà racine dans ses premières œuvres. Dans des petits objets et installations, Villiger s’inspire de l’arte povera en leur donnant un biais féministe. Ainsi, les formes de dards et de lancettes en matériau végétal, qu’elle expose en 1975 à la Biennale des Jeunes à Paris et plus tard au Tessin lors de la G’76 à Vira Gambarogno, renferment une note explicitement sexospécifique. Des moments d’agression et de menace transparaissent également dans ces ouvrages – des aspects qui font leur apparition dès 1974 dans l’écorçage de branches et de troncs et préfigurent en même temps le corps nu, qui se montre brut et vulnérable.

Comme l’attestent les exemples, Villiger se présente au début comme plasticienne. Selon le principe «moi avec l’objet», elle conserve cette image de soi même lorsque la photographie devient de plus en plus centrale et finalement l’unique instrument de ce questionnement artistique. Cette exclusivité est atteinte en 1980 lorsque Villiger cesse de diriger son petit appareil photo sur des motifs fugaces souvent éloignés. A la place, elle prend désormais la plupart du temps un appareil Polaroïd avec lequel elle agit sous un rayon étroit. D’une part cela produit des séries qui documentent la vue depuis l’atelier ou une autre pièce de vie sur les alentours immédiats. D’autre part commence l’étude intensive de son propre corps qui – comme l’art corporel – demande aussi une forme de représentation moderne du fait du choix du médium. Dès 1980, cette pratique se consolide à l’occasion de l’exposition «4.1» à l’Aargauer Kunsthaus avec les premiers tirages chromogènes en grand format à l’aide d’internégatifs. La petite photo instantanée devient ainsi un manifeste confrontatif. En 1983, lorsque le corps dénudé acquiert plus de visibilité, les dimensions sont une nouvelle fois agrandies au nouveau standard de 125 x 123 cm, un format qui ne sera plus que très rarement réduit, comme ici où le bloc trouve son équilibre avec des panneaux un peu plus petits de 105 x 108 cm. De plus, le titre jusqu’alors uniforme de «Arbeit» laisse la place à la dénomination «Skulptural» qui s’applique dès lors à tous les blow-ups de motifs corporels montrés individuellement.

Dans l’intimité de son atelier, Villiger se photographie ou plus exactement photographie désormais avec son SX70 des parties de son corps remplissant très souvent toute l’image: tantôt de très près, tantôt d’aussi loin que le bras tendu le lui permet. Son obstination à vouloir appuyer elle-même sur le déclencheur a l’avantage que la morphologie connue des membres se désagrège – en partie par le recours à un miroir – dans la vision de près. Totalement exempte d’un amour de soi narcissique, Hannah Villiger déjoue ainsi les conventions du beau et du provocant: le nu féminin, que le regard masculin, sourdement ou ouvertement voyeuriste, a engendré au fil des siècles, se voit décomposé de par le rendu fragmenté. Une image du corps prend alors place, qui part certes de sa propre existence subjective mais qui devient finalement un corps anonyme, un corps en soi dont la perception se laisse guider activement ou former, selon Villiger, pour ainsi dire en sculpture au cours d’un dialogue avec soi-même.

Ce faisant, l’auto-observation de Villiger, qui a commencé en 1980, l’année où elle a contracté la tuberculose ouverte, connaît une véritable métamorphose. Alors qu’au début les travaux sont encore empreints de désir érotique et de métaphores d’émotions vacillantes, la perspective tâtonnante, appréhendant le corps de manière presque topographique, s’impose de plus en plus rapidement. Des moments de dissolution transparente alternent avec une affirmation de soi d’une franchise désarmante qui s’exprime aussi dans certaines poses prises. En revanche, l’approche des fragments d’images s’avère tout à fait instable. Parfois, la désorganisation du corps va si loin qu’il en résulte même une plurivocité à peine déchiffrable. Dans l’accrochage en blocs, tel que l’artiste le pratique pour la première fois en 1981 et depuis 1988 le pourvoit d’un titre, en commençant par la présente œuvre, la boucle se referme: «[…] forte présence; multiplication, ce doit être un tout et chaque élément doit fonctionner indépendamment.»

Astrid Näff, 2021

***

Con “Block I” (Blocco I), il primo lavoro fotografico di grande formato di Hannah Villiger (1951-1997), composto esclusivamente da vedute frammentarie del proprio corpo, l’Aargauer Kunsthaus custodisce un importante lavoro di svolta dell’artista. L’opera è datata 1988, ma l’idea di femminilità basata sulla considerazione della pelle e delle parti del corpo come materiale di un’indagine scultorea autonoma, risale al periodo d’esordio. Nei primi lavori, costituiti da piccoli oggetti e installazioni, Villiger ottiene importanti impulsi dall’Arte Povera, virati in chiave femminista. Le forme lanceolate di materiale vegetale, presentate nel 1975 alla Biennale des Jeunes a Parigi e un anno dopo alla G’76 a Vira Gambarogno in Ticino, sottendono un esplicito riferimento di genere. In questi lavori risuonano però anche momenti di aggressione e di pericolo – aspetti affiorati già nel 1974, nei lavori basati sullo scortecciamento di rami e tronchi che nel contempo anticipano il corpo nudo, reso manifesto nella sua naturalità e fragilità.

Fin dall’inizio del suo percorso, Villiger si considera una scultrice. In base al principio “io con l’oggetto”, conserva questa identità anche quando la fotografia si afferma progressivamente come medium dominante e infine esclusivo della sua pratica artistica. L’approdo all’utilizzo del mezzo fotografico si situa nel 1980, quando Villiger cessa di orientare la sua fotocamera di piccolo formato verso motivi sfuggenti e spesso distanti, a favore di macchine polaroid e di un raggio di azione molto più ristretto. In seguito, realizza da un lato dei lavori in serie che documentano lo sguardo da casa o dallo studio sull’ambiente circostante, mentre dall’altro avvia un’intensa indagine incentrata sul proprio corpo, che analogamente alla Body Art interroga, attraverso il mezzo fotografico, anche la forma contemporanea della rappresentazione come tale. Già nel 1980 questa pratica si consolida nei primi esempi di stampe cromogeniche di grande formato, realizzate con l’aiuto di internegativi, presentati in occasione della mostra “4.1.” all’Aargauer Kunsthaus. In questi lavori la piccola istantanea privata diventa un manifesto critico. Nel 1983, quando il corpo nudo passa in primo piano, le dimensioni vengono ulteriormente ampliate al nuovo standard di 125 x 123 cm, che in seguito lascia raramente spazio a formati più piccoli, come nell’opera in esame, costituita da elementi di 105 x 108 cm ciascuno. Il titolo invariato “Arbeit” (Lavoro), utilizzato finora, viene sostituito dalla designazione “Skulptural” (Scultoreo), adottata d’ora in avanti per tutti i particolari ingranditi di motivi corporei.

Nell’intimità dello studio, con la sua SX70 Villiger fotografa se stessa, o meglio parti del suo corpo, in modo da riempire l’intera superficie dell’immagine: talvolta in primissimo piano, altre volte alla distanza consentita dal braccio teso. La sua insistenza a premere il pulsante di scatto in prima persona facilita – talora con l’aiuto di specchi – la disgregazione della familiare sintassi corporea in inquadrature ravvicinate. Totalmente affrancata da inclinazioni narcisistiche, Hannah Villiger mina così le convenzioni della bellezza e della seduzione. Il nudo femminile, generato per secoli dallo sguardo maschile implicitamente o apertamente voyeuristico, viene smembrato per mezzo della frammentazione. Al suo posto subentra un’immagine corporea, che per quanto proveniente dalla propria esistenza soggettiva diventa un corpo anonimo, un corpo di per sé, la cui percezione si lascia guidare attivamente e – secondo l’artista – un corpo che attraverso il dialogo con se stesso si lascia plasmare in termini scultorei.

L’auto-osservazione avviata dall’artista nel 1980, l’anno in cui si ammala di tubercolosi aperta, conosce nel tempo una chiara metamorfosi. Se in principio prevalgono il desiderio erotico e le metafore di stati d’animo mutevoli, in seguito si impone rapidamente e in misura crescente lo sguardo aderente al corpo come per esplorarlo in termini topografici. Momenti di dissoluzione e frantumazione si alternano a una ricerca di identità, disarmante nella sua immediatezza, che traspare anche da numerose pose assunte. L’utilizzo di particolari corporei si rivela invece piuttosto instabile. A volte la disorganizzazione del corpo viene accentuata fino a ottenere un’ambiguità visiva quasi indecifrabile. Nell’accostamento delle immagini in “blocchi” – sperimentato dal 1981 e a partire dall’opera in esame menzionato nel titolo – i singoli particolari vengono ricongiunti in una nuova unità: “[…] presenza intensa; moltiplicazione, deve essere un tutt’uno e ogni parte deve funzionare in maniera autonoma.”

Astrid Näff, 2021