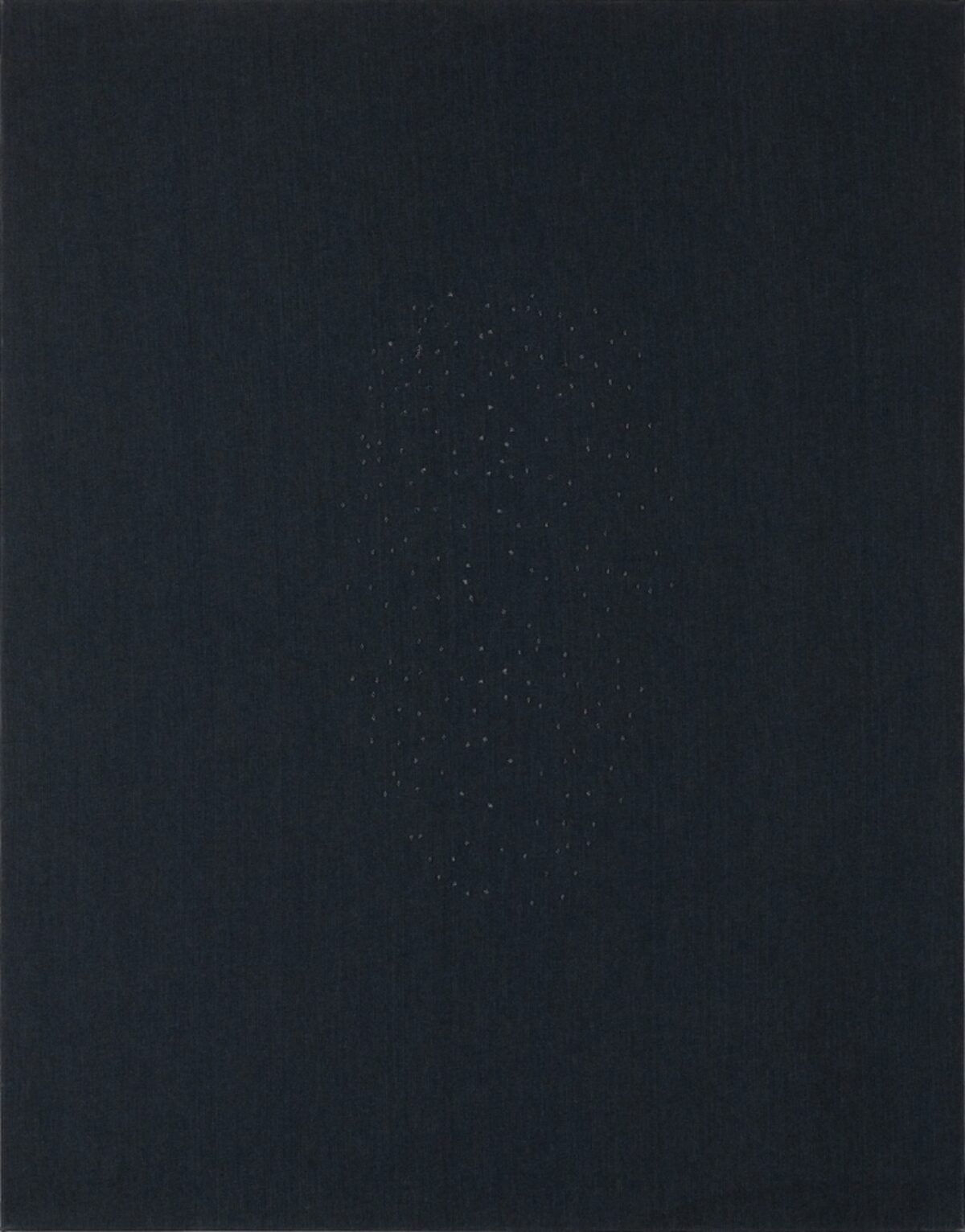

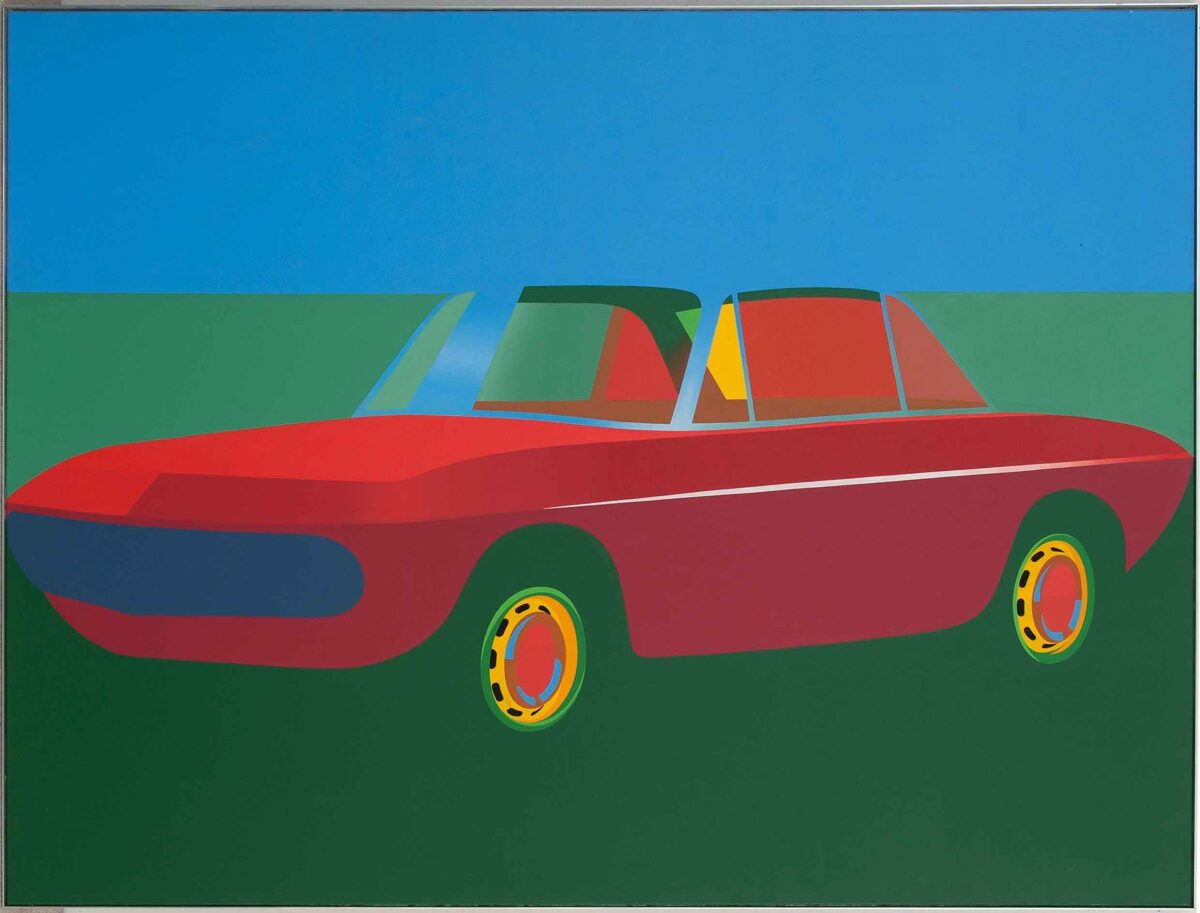

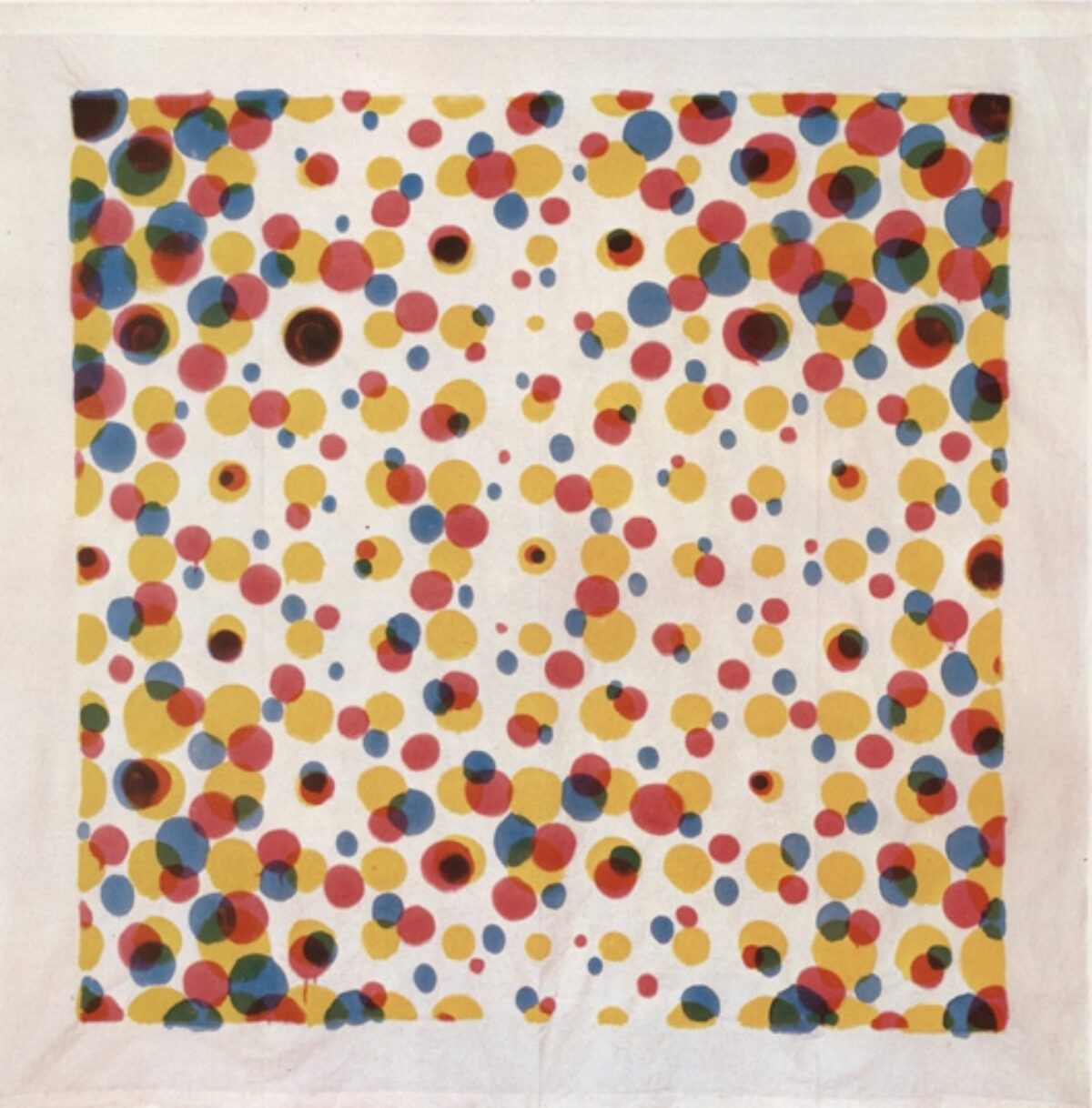

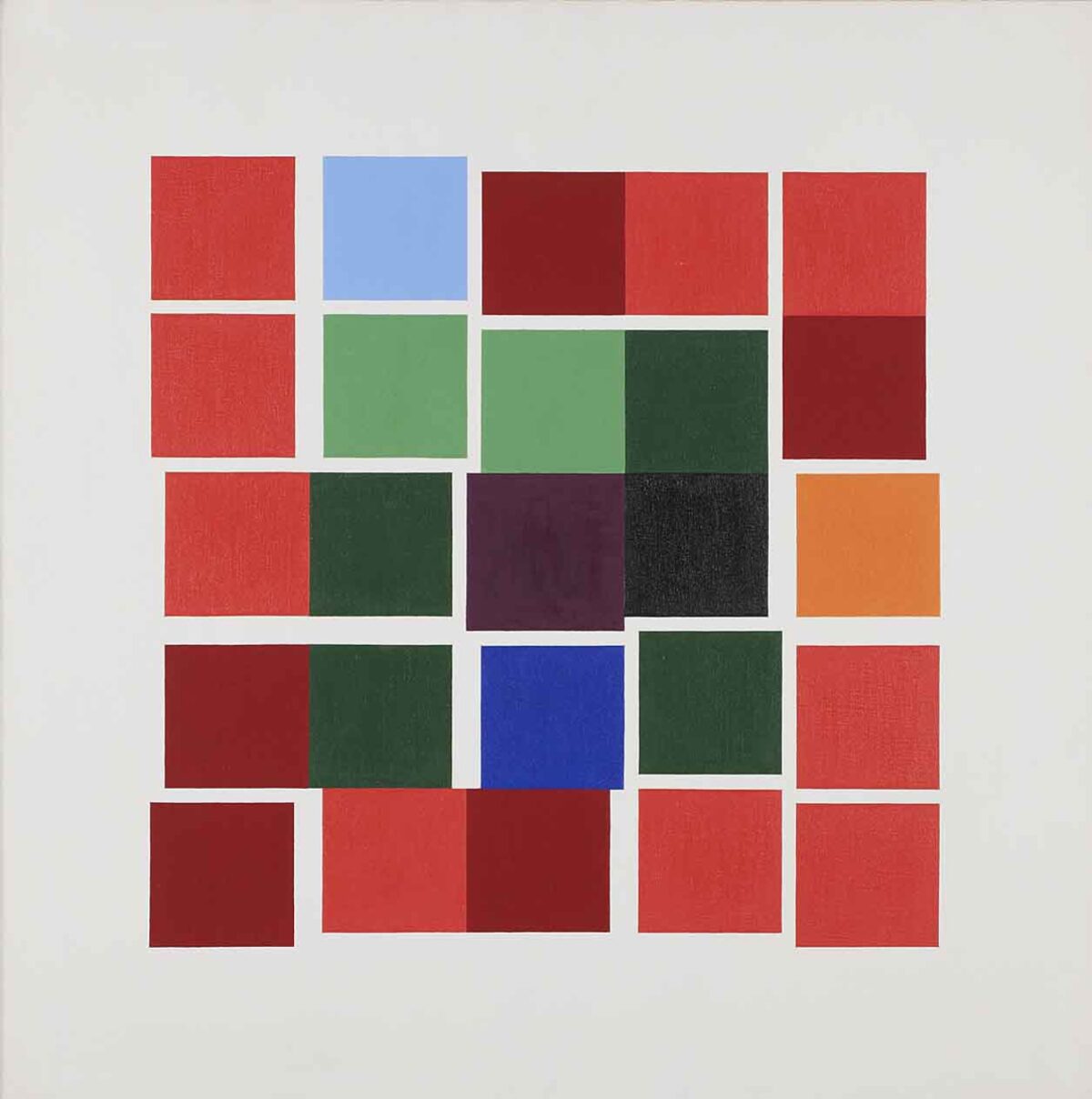

Öl auf Leinwand, 77 x 77 cm

English, french and italian version below

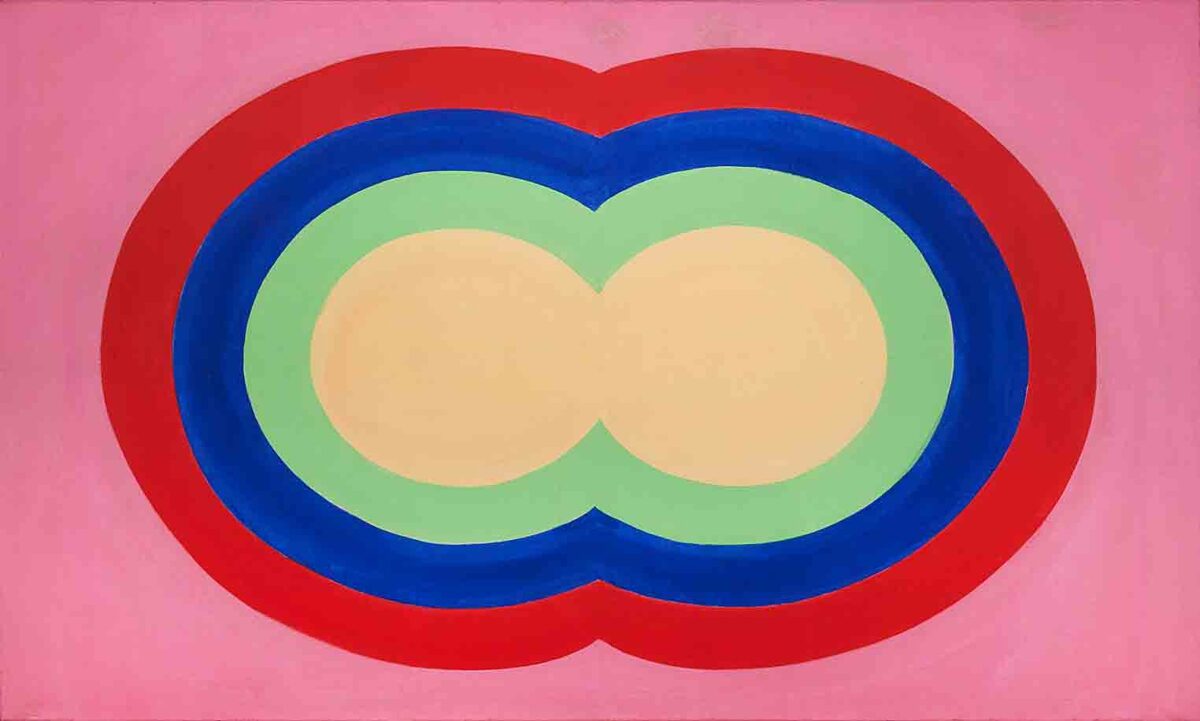

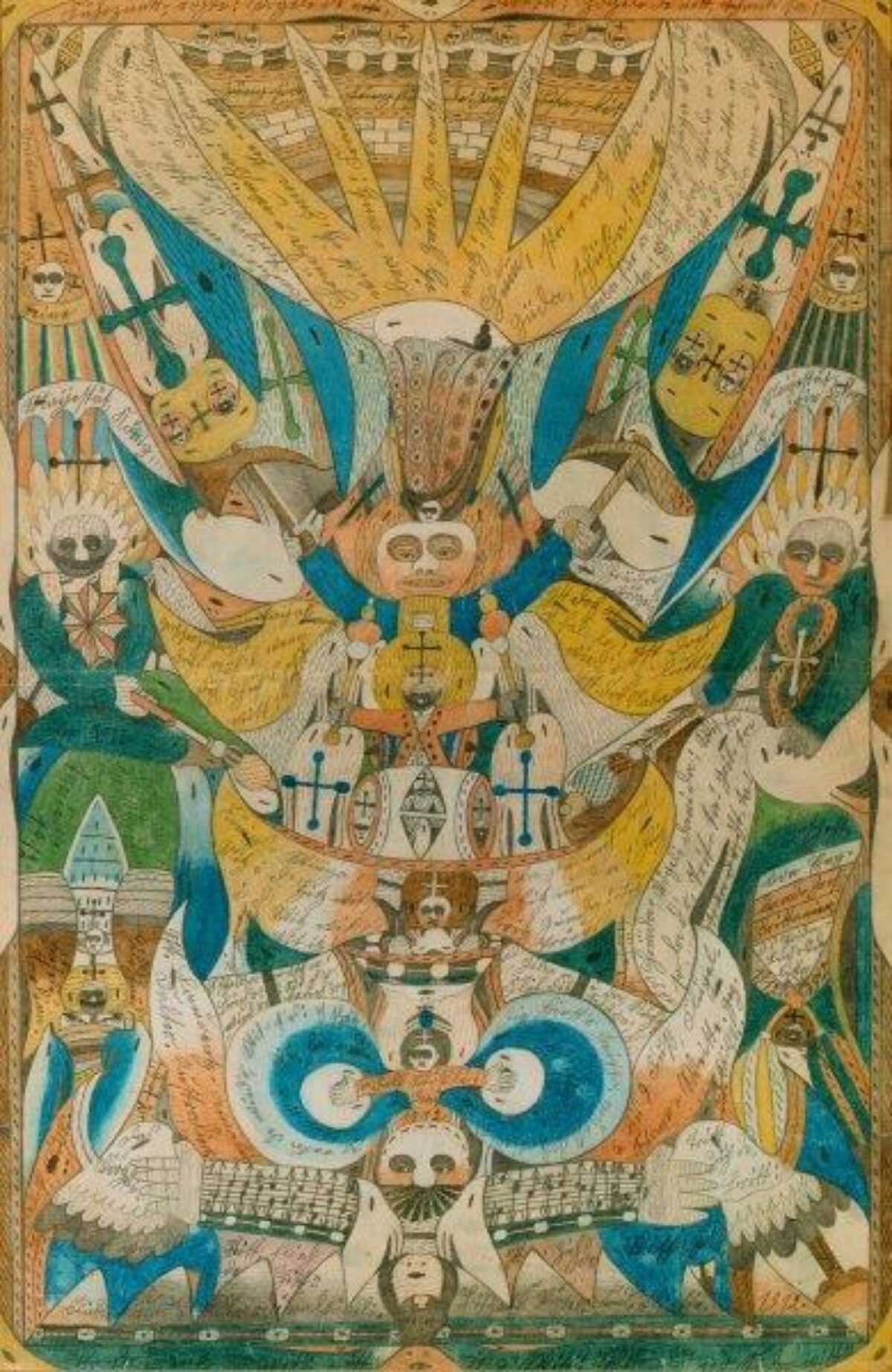

In der Sammlung des Aargauer Kunsthauses bildet die hochwertige Werkgruppe der konkreten Kunst eine Brücke zwischen der historischen Abteilung und dem Bereich der zeitgenössischen Kunst. Verena Loewensberg (1912–1986) gehört zusammen mit Max Bill (1908–1994), Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988) und Camille Graeser (1892–1980) zu den Schweizer Hauptvertretern der konstruktiv-konkreten Kunst, deren Entwicklung durch die politischen Geschehnisse im übrigen Europa unterdrückt wird. Die Zürcher Konkreten führen diese Kunstrichtung fort und systematisieren sie. Durch ihre Arbeit wird Zürich von 1936 bis in die 1950er-Jahre zu einem Zentrum der konkreten Kunst, die mit ihrer Präzision, Schnörkellosigkeit und Sauberkeit dem Bild der modernen Schweiz der Nachkriegszeit und der damals vorherrschenden Ideologie der „Guten Form“ entspricht.

Innerhalb der Gesinnungsgemeinschaft der Zürcher Konkreten nimmt Loewensberg eine aussenstehende Position ein: Sie ist die einzige Frau, verzichtet auf Theorieformulierungen und zeigt im Umgang mit Gesetzmässigkeiten einen freieren Umgang als ihre Künstlerkollegen. Sie hält sich fern von öffentlichen Diskussionen und konzentriert sich auf ihre eigenen Werke. Diese Umstände mögen ausschlaggebende Gründe dafür sein, dass sich ihre Anerkennung im Gegensatz zu ihren Kollegen um Jahrzehnte verzögert, obwohl es ihr an Unterstützung seitens der Zürcher Konkreten nicht fehlt. In den 1950er-Jahren spielt sie die Themen Rhythmus und Bewegung mit grösseren Formgruppierungen durch. Das vorliegende Sammlungswerk „Ohne Titel“ ist ein auffälliges Beispiel für den Aspekt der Rhythmisierung. Fünfundzwanzig Quadrate – neben Grün- und Blautönen sind rote Nuancen vorherrschend – ordnen sich zu einem vibrierenden Farbfeld.

Während Bill und Lohse mit den Titeln ihrer Werke die konstruktive Bildlösung an sich bezeichnen, erachtet Loewensberg Titel als „Belastung für das Werk und für dessen Betrachter, weil Vorstellungen vorweggenommen würden“. Wie die meisten ihrer Arbeiten ist auch dieses mit Ölfarben gemalt. Bemüht um handwerkliche Perfektion, die Teil ihrer künstlerischen Auffassung bildet, hält sich die Künstlerin an einen strengen Arbeitsablauf. Sie verzichtet auf das Abklebeverfahren und erarbeitet sich Bildkonstruktion und Bildformat mit kleinen Konstruktionsstudien auf Millimeterpapier. Sobald diese feststehen, vergrössert sie den Entwurf auf den Massstab 1:1 und legt ihn auf die grundierte Leinwand. Wichtige Stellen werden mit der Zirkelspitze punktiert, die Fläche wird mit Bleistift und Lineal unterteilt. Anschliessend beginnt der eigentliche Malprozess: Die Künstlerin trägt die Farben in mehreren Schichten dünn auf, bis die gewünschte Intensität erreicht ist. Die vorbereitenden Zeichnungen sind für Loewensberg Mittel zum Zweck. Sie hat sie in der Regel nach Gebrauch entsorgt.

Das Aargauer Kunsthaus realisierte 1992 eine Retrospektive der Künstlerin; in ihrem Nachgang konnte das Bild „Ohne Titel“ erworben werden.

Karoliina Elmer

***

In the collection of the Aargauer Kunsthaus, the group of high-quality works of Concrete art forms a bridge between the historical and contemporary art sections. Along with Max Bill (1908–1994), Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988) and Camille Graeser (1892–1980), Verena Loewensberg (1912–1986) is one of the Swiss protagonists of constructive and Concrete art, a movement whose development in the rest of Europe was suppressed due to the political events of the period. The Zurich Concretes continued this movement and systematised it. Owing to their work, Zurich became a centre of Concrete art from 1936 to the 1950s. The precision, simplicity and cleanliness of this art was consistent with the image of modern, post-war Switzerland and the ideology of “good form” that was prevalent at the time.

Loewensberg was an outsider within the community of convictions of the Zurich Concretes: She was the only woman, she refrained from formulating theories and she was less rigid than her fellow artists in her approach to laws. She avoided public debates and focused on her own works. Those circumstances may be the main reason why, unlike her colleagues, her recognition was delayed by decades, even though she did not lack support from the Zurich Concretes. In the 1950s she experimented with variations on the themes of rhythm and movement using larger groups of forms. “Untitled”, the work in our collection, is a striking example of the aspect of rhythmisation. Twenty-five squares – besides greens and blues, reds predominate – form a vibrating colour field.

While Bill and Lohse gave their works titles referring to the particular constructive pictorial solution itself, Loewensberg considered titles “a burden for the work and for its viewer, because ideas would be anticipated”. Like most of her paintings, this canvas is done in oil. Striving for technical perfection, which was part of her artistic understanding, the artist adhered to a strict working process. Foregoing masking, she worked on pictorial construction and image format in small studies on graph paper. Once these were established, she enlarged the drawing to a scale of 1: 1 and placed it on the primed canvas. Important spots were punctured with the point of a compass and the surface was divided up with pencil and ruler. Then the actual painting process began: the artist applied the paint thinly in several layers until the desired intensity was reached. For Loewensberg, the preparatory drawings were a means to an end; she usually disposed of them after use.

***

o Dans les collections de l’Aargauer Kunsthaus, l’ensemble d’œuvres de haute qualité représentant l’art concret constitue une passerelle entre le département historique et la zone dédiée à l’art contemporain. Verena Loewensberg (1912–1986) fait partie, avec Max Bill (1908–1994), Richard Paul Lohse (1902–1988) et Camille Graeser (1892–1980), des principaux représentants suisses de l’art concret constructiviste, dont le développement fut étouffé dans le reste de l’Europe en raison des évènements politiques. Les concrets zurichois continuent à faire vivre ce mouvement artistique et le systématisent. Grâce à leur travail, Zurich devient dès 1936 et jusque dans les années 1950 un centre de l’art concret qui, avec sa précision, son absence de fioriture et sa netteté, correspond à l’image de la Suisse moderne de l’après-guerre et à l’idéologie, dominante à l’époque, de la «bonne forme».

o

Au sein des concrets zurichois, groupe défendant les mêmes conceptions, Loewensberg occupe une place à part: elle est la seule femme, renonce à formuler des théories et fait preuve d’une plus grande liberté que ses collègues dans l’application des préceptes. Elle se tient à distance des discussions publiques et se concentre sur ses propres œuvres. Ces circonstances permettent vraisemblablement d’expliquer pourquoi, contrairement à ses collègues, elle ne fut reconnue que des décennies plus tard alors qu’elle ne manquait pas de soutien de la part des concrets zurichois. Dans les années 1950, elle décline sous tous leurs aspects le rythme et le mouvement avec des groupes de formes de taille assez importante. La présente œuvre de nos collections, «Ohne Titel», est un exemple frappant de la rythmicité. Vingt-cinq carrés – outre les tons verts et bleus, les nuances de rouge sont dominantes – s’agencent en un champ de couleurs vibrantes.

Alors que Bill et Lohse dévoilent en fait la solution de l’image constructiviste dans le titre de leurs œuvres, Loewensberg considère les titres comme «un fardeau pour le tableau et le spectateur, car ils influent sur son imagination». Comme la plupart de ces toiles, celle-ci est également réalisée avec des peintures à l’huile. Soucieuse d’un travail de perfection, ce qui fait partie de sa conception artistique, l’artiste s’astreint à un processus strict. Elle renonce au procédé de masquage et élabore la structure figurative et le format du tableau à partir de petites études de conception sur du papier millimétré. Lorsque cela est acquis, elle agrandit l’ébauche à l’échelle 1:1 et la place sur la toile apprêtée. Les endroits importants sont marqués à l’aide de la pointe d’un compas, la surface est divisée en utilisant une règle et un crayon graphite. C’est ensuite que commence le processus de peinture proprement dit: l’artiste applique les couleurs en plusieurs couches fines jusqu’à obtenir l’intensité souhaitée. Pour Loewensberg, les dessins de préparation sont un moyen d’atteindre un but. En général, elle les a détruits après usage.

En 1992, l’Aargauer Kunsthaus a réalisé une rétrospective de l’artiste, qui a permis ensuite d’acquérir le tableau «Ohne Titel».

Karoliina Elmer

***

o Nella collezione dell’Aargauer Kunsthaus il ragguardevole gruppo di opere di arte concreta funge da ponte tra la sezione storica e l’ambito contemporaneo. Insieme a Max Bill (1908-1994), Richard Paul Lohse (1902-1988) e Camille Graeser (1892-1980), Verena Loewensberg (1912-1986) è tra i principali esponenti svizzeri dell’arte costruttivista-concreta, che a seguito degli eventi politici viene repressa nel resto dell’Europa. I concretisti zurighesi proseguono questa corrente artistica, sistematizzandola. Grazie alle loro ricerche, dal 1936 agli anni Cinquanta Zurigo diventa un centro dell’arte concreta, che con la sua precisione, nitidezza e sobrietà corrisponde all’immagine della Svizzera moderna del dopoguerra e all’ideologia allora imperante della “buona forma”.

All’interno del sodalizio di idee dei concretisti zurighesi, Loewensberg occupa una posizione a sé stante: è l’unica donna, rinuncia alla formulazione di teorie e mostra maggiore libertà nell’utilizzo delle regole rispetto ai suoi colleghi. Non prende parte alle discussioni pubbliche e si concentra sulle proprie opere. Queste scelte spiegano forse il suo riconoscimento tardivo, in ritardo di qualche decennio rispetto ai concretisti zurighesi, dai quali ha peraltro sempre ricevuto sostegno e incoraggiamento. Negli anni Cinquanta esplora a fondo i temi del ritmo e del movimento per mezzo di raggruppamenti formali più complessi. L’opera Ohne Titel (Senza titolo) conservata nella collezione argoviese rappresenta un esempio particolarmente evidente di ritmizzazione. Venticinque quadrati – accanto ai toni verdi e blu prevalgono tinte rosse – sono disposti a formare un vibrante campo cromatico.

Se Bill e Lohse utilizzano la titolazione delle opere per descrivere la costruzione delle loro soluzioni iconografiche, Loewensberg considera il titolo un “condizionamento per l’opera e lo spettatore, poiché prevarica l’immaginazione”. Come la maggior parte dei suoi lavori, anche Ohne Titel è dipinto a olio. Alla ricerca della perfezione artigianale, quale parte integrante della sua concezione artistica, Loewensberg osserva un procedimento di lavoro rigoroso. Rinuncia all’uso del nastro adesivo e sviluppa la costruzione e il formato del quadro per mezzo di piccoli studi costruttivi su carta millimetrata. Quando la soluzione è definitiva, ingrandisce il progetto in scala 1:1 e lo traspone sulla tela preparata. I punti importanti vengono segnati con la punta del compasso, mentre la superficie viene suddivisa a matita con l’aiuto di un righello. A questo punto prende avvio il processo pittorico vero e proprio: l’artista applica i colori a strati sottili, fino a raggiungere l’intensità desiderata. I disegni preparatori sono per Loewensberg un mezzo per un fine: dopo il loro utilizzo, di regola vengono eliminati.

L’opera Ohne Titel è stata acquistata dall’Aargauer Kunsthaus in margine alla retrospettiva dell’artista presentata al museo nel 1992.

Karoliina Elmer

In 1992, the Aargauer Kunsthaus organised a retrospective of the artist and was subsequently able to acquire the painting “Untitled”.

Karoliina Elmer

***