Videoinstallation,

English, french and italian version below

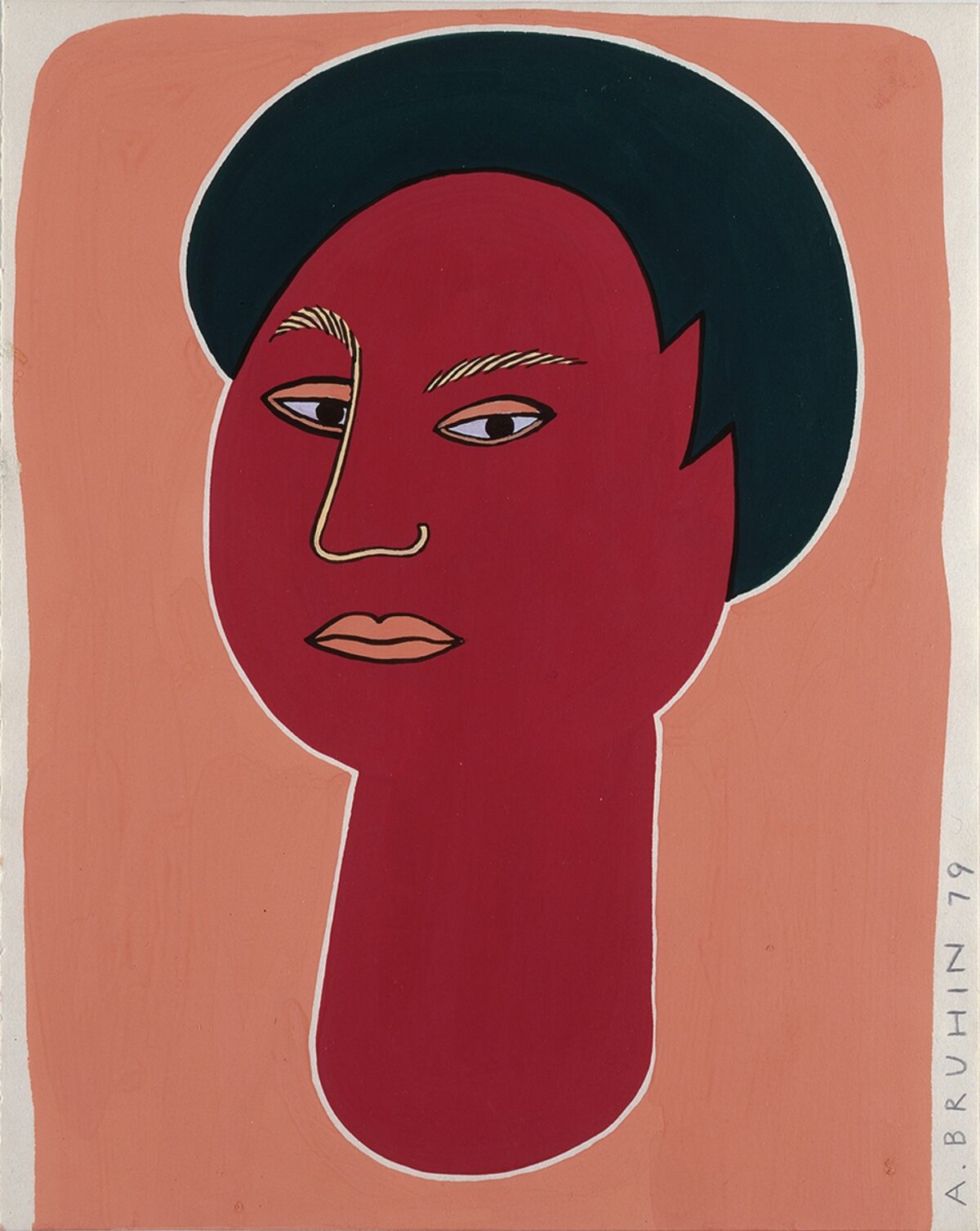

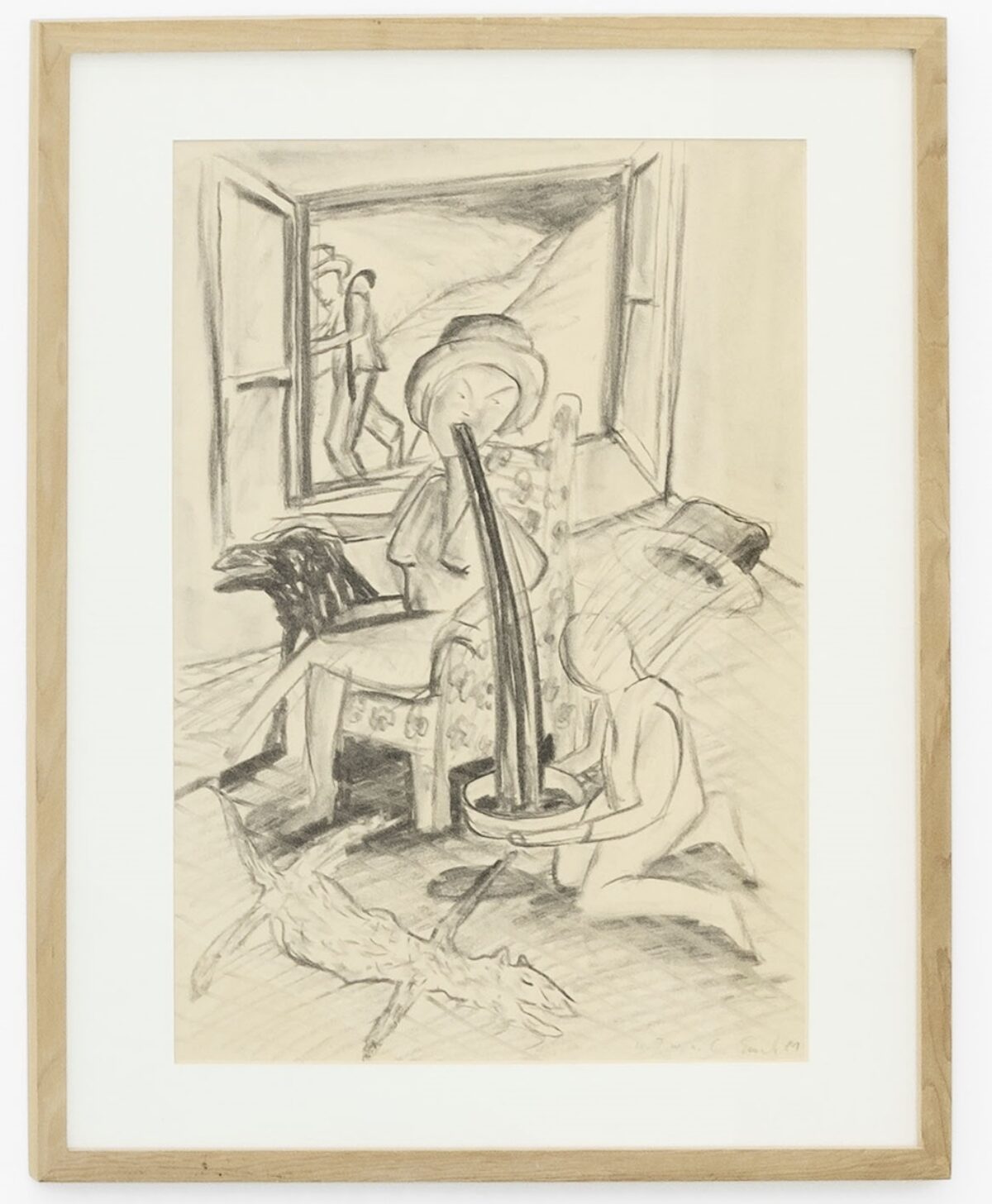

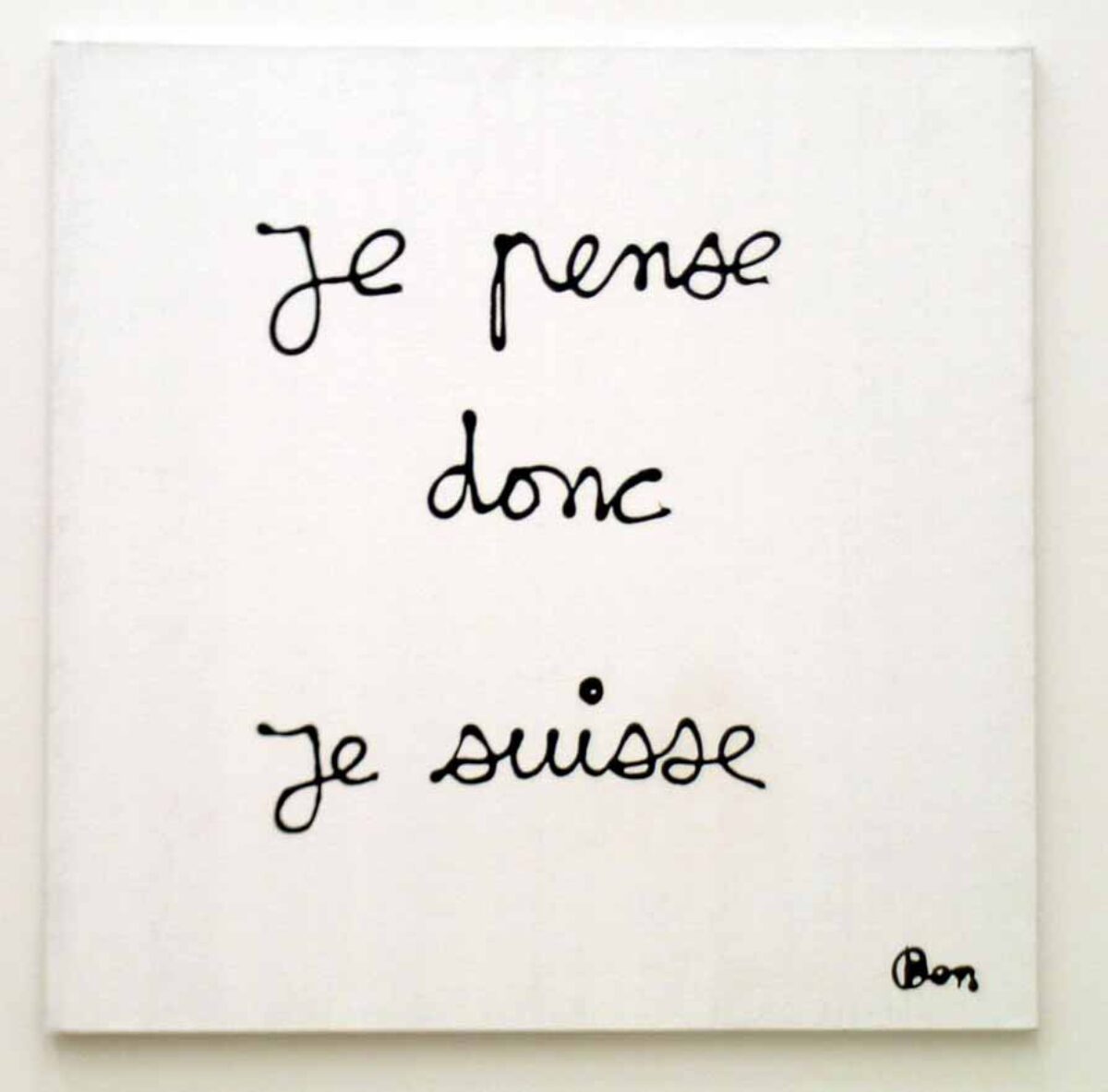

In unterschiedlichen Medien schafft Zilla Leutenegger (*1968) ihren ganz eigenen Werkkosmos rund um „Zilla“, das Alter Ego der Künstlerin und zugleich „Exempel für den Menschen“. Mit einer kindlichen Unvoreingenommenheit spürt sie den einfachen, aber umso existenzielleren Fragen des Alltagslebens nach. So schafft sie in ihren Zeichnungen, Videoinstallationen und Skulpturen Szenerien, in denen wir uns wiedererkennen: „Zilla sind viele“, schreibt der Kritiker Hans Rudolf Reust, und dementsprechend häufig sprechen uns Leuteneggers Arbeiten direkt aus dem Herzen.

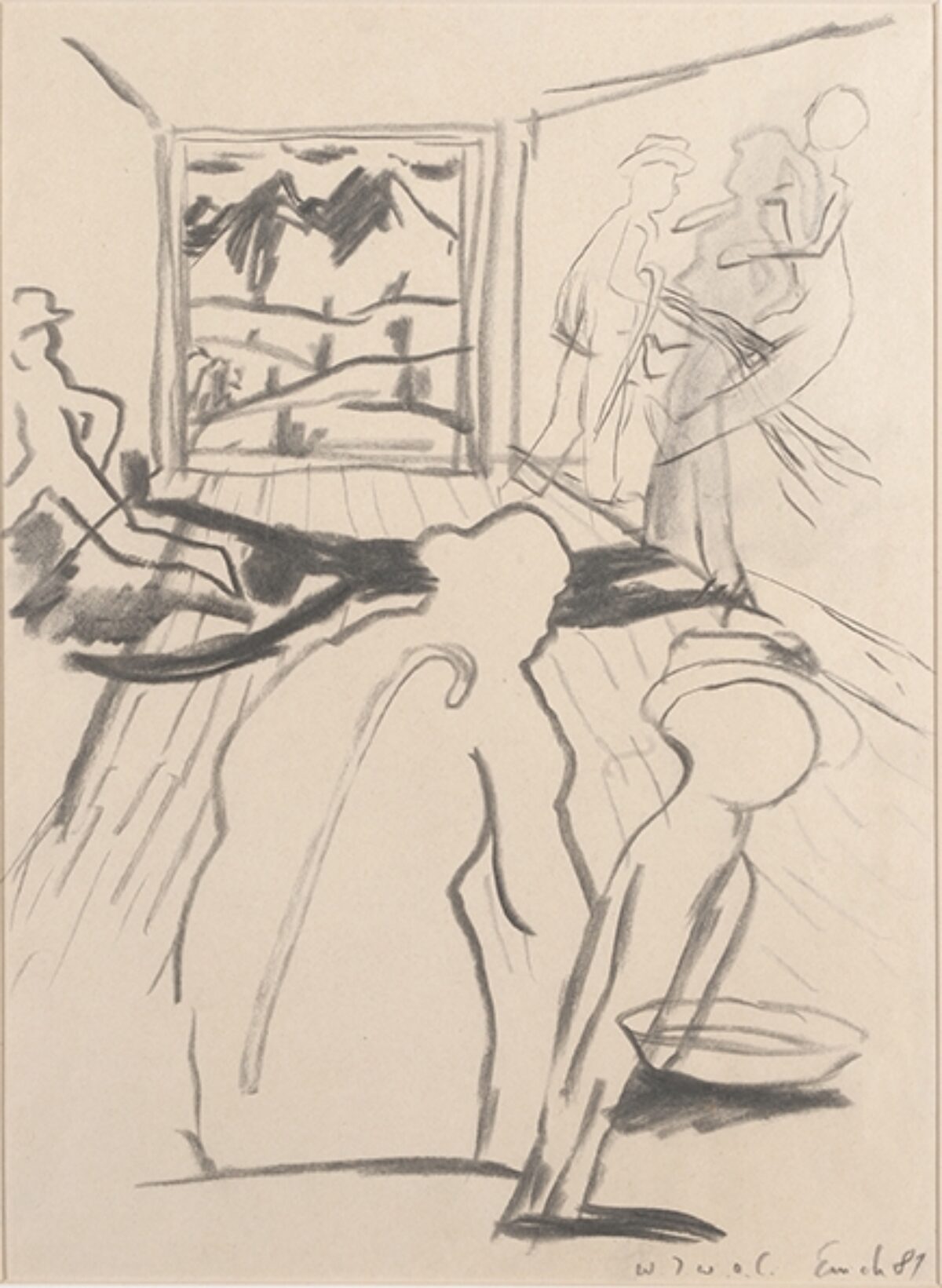

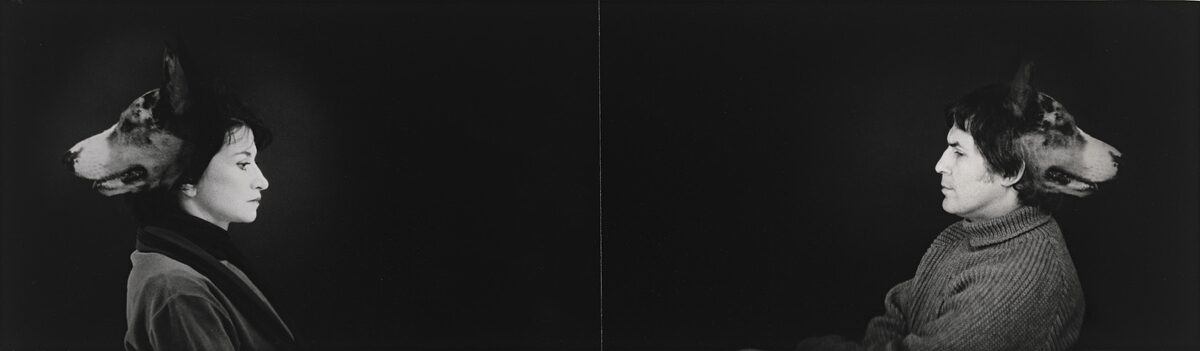

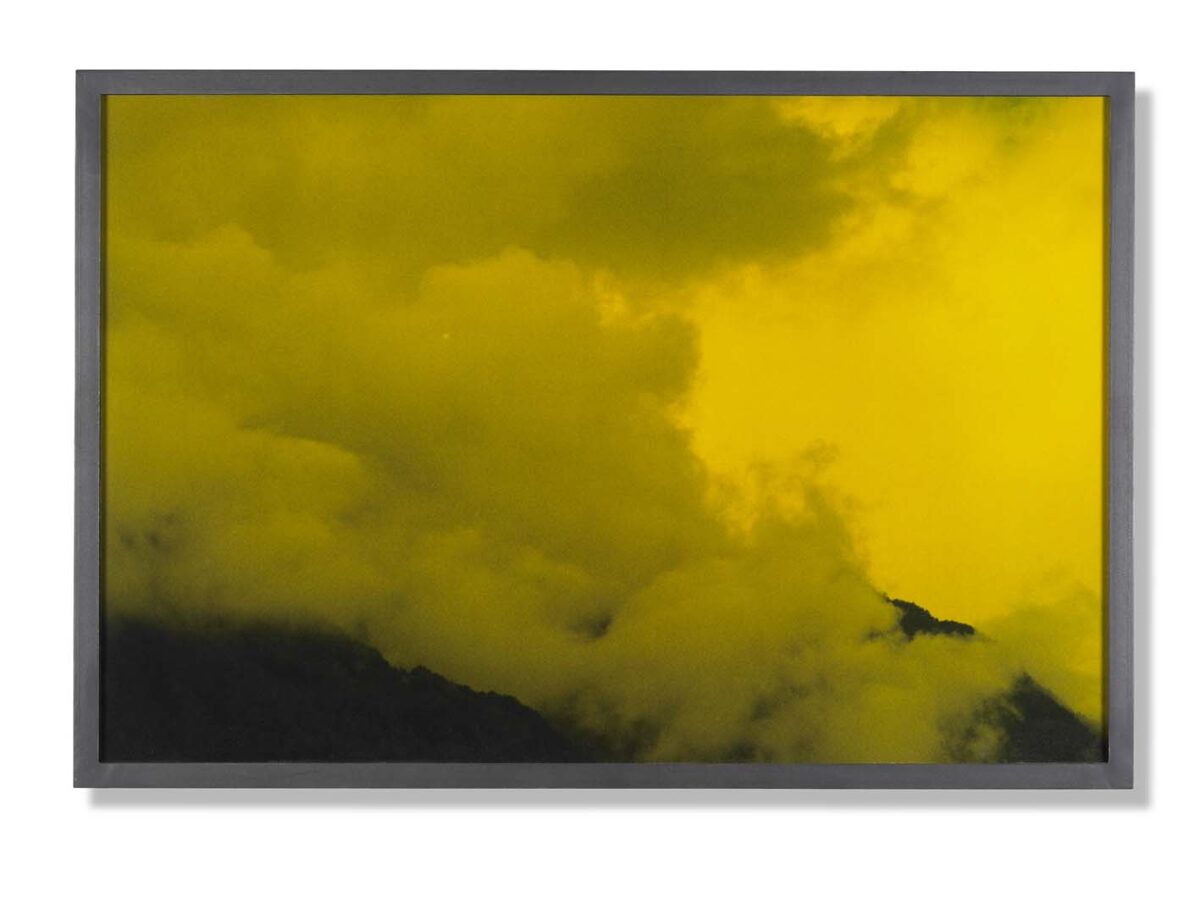

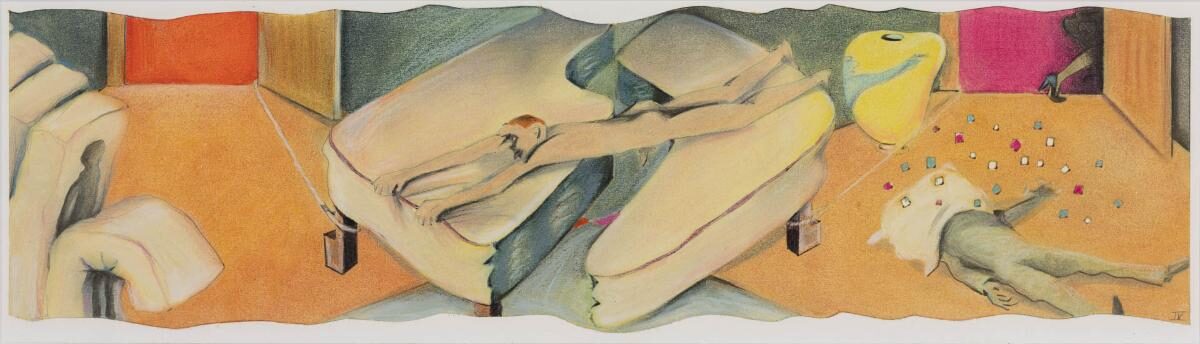

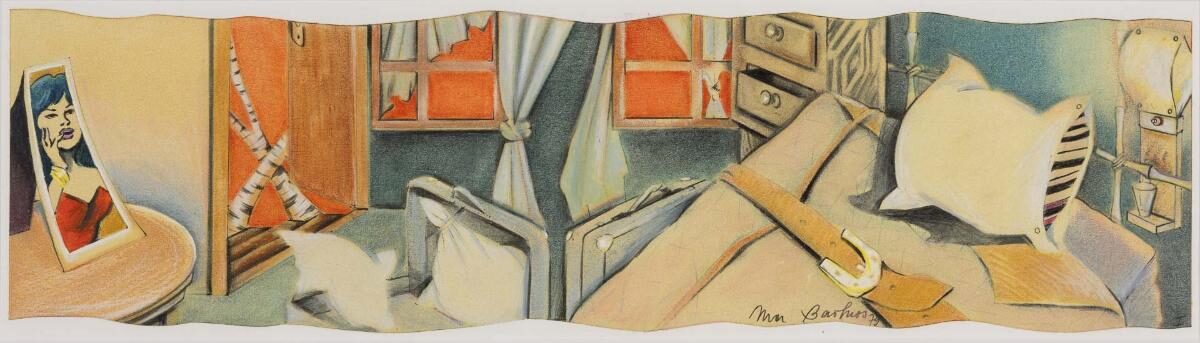

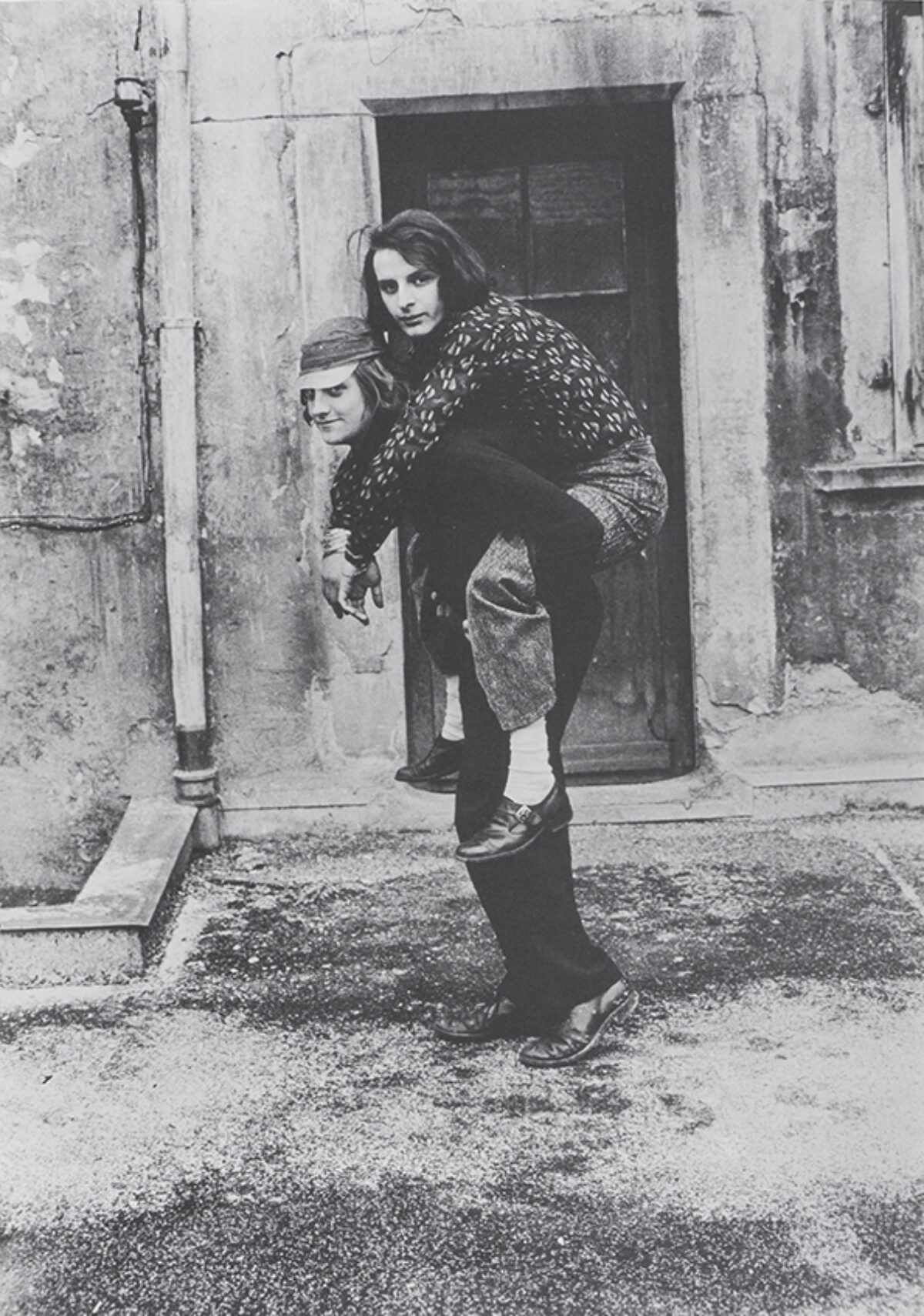

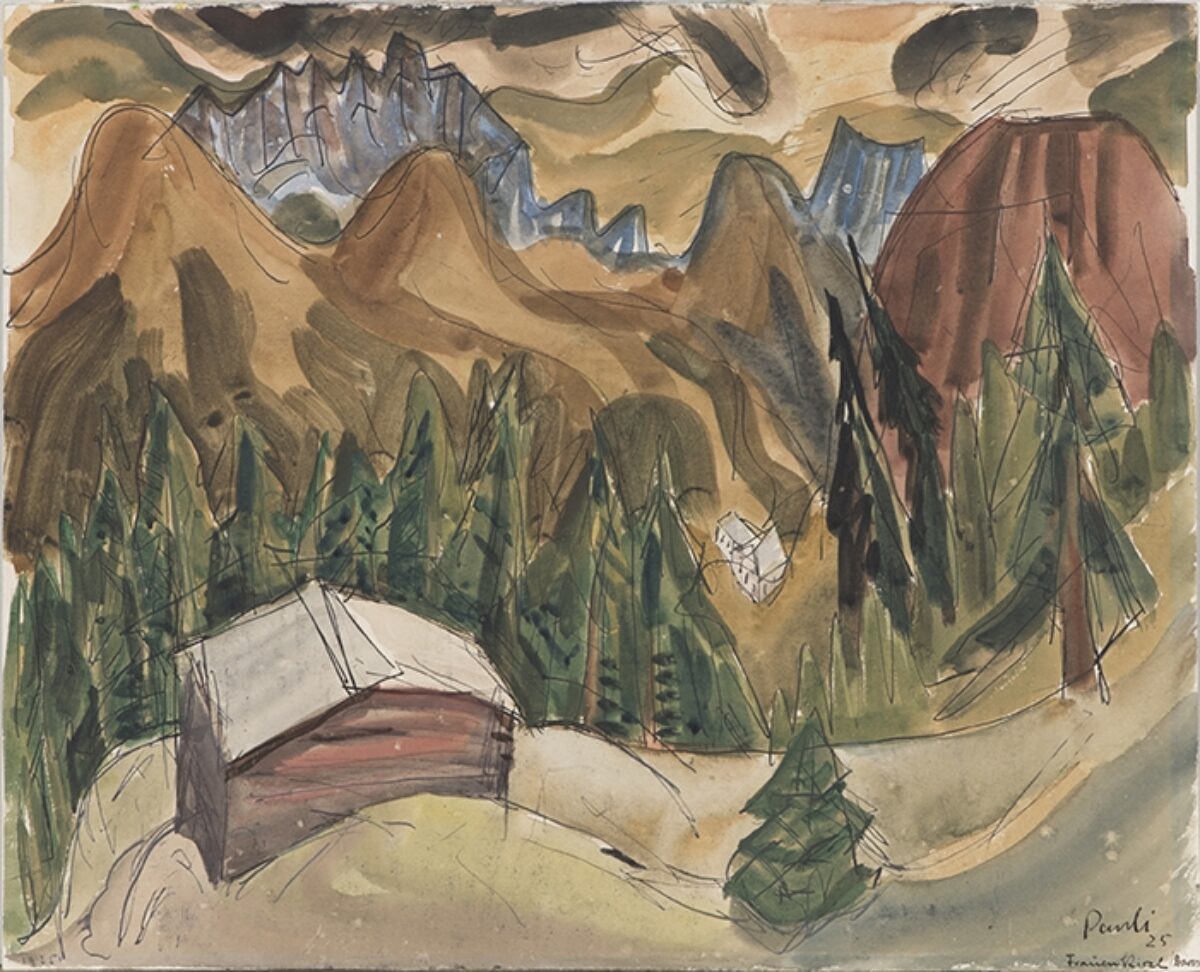

Sowohl Erinnerungen an die eigene Vergangenheit als auch Fragen zur weiblichen Identität sind wiederkehrende Motive in Leuteneggers Werken. Beide Sphären finden Eingang in die Videoinstallation „Der Mann im Mond“ aus dem Jahr 2000, die mithin zu den bekanntesten Arbeiten der Künstlerin zählt und 2002 für die Sammlung des Aargauer Kunsthauses erworben wird. Wir finden uns in einer schwarz-weissen Mondlandschaft wieder: mittendrin ein riesiger Krater, im Hintergrund ein golfwagenähnliches Gefährt und am Kraterrand die Künstlerin selbst in sportlichem Outfit und mit Mütze. Breitbeinig steht sie da, wippt sanft von den Fersen auf die Fussspitzen und pinkelt wie ein Mann in hohem Bogen in den Krater hinein, was uns unweigerlich ein Schmunzeln entlockt. Dazu pfeift sie unablässig die Melodie aus „Spiel mir das Lied vom Tod“ vor sich hin. Die Szenerie wird vom Schein der Erdkugel erhellt, die als einziges farbiges Element per Dia auf den Videohimmel projiziert ist. Eine Kindheitserinnerung steckt in den Ursprüngen der Arbeit: Als kleines Mädchen stellt sich Leutenegger vor, ihr Vater lebe auf dem Mond, als er ihr aus Texas eine Postkarte schickt, die die Mondlandung zeigt. Offensichtlich sind aber auch parodistische Elemente im Video: der furchtlose Western-Held, oder der Mann, der im Pinkeln sein Terrain markiert, sowie die Mondlandung als einer der grössten Meilensteine der Geschichte des 20. Jahrhunderts – all diese eindeutig männlich konnotierten Assoziationen eignet sich Leutenegger selbstbewusst an und demaskiert sie mit einer für ihre Arbeit typischen, umwerfend liebevollen Ironie. Während die Künstlerin charmant den männlichen Habitus mimt, symbolisiert hoch am Himmel die leuchtende „Mutter Erde“ das Weibliche.

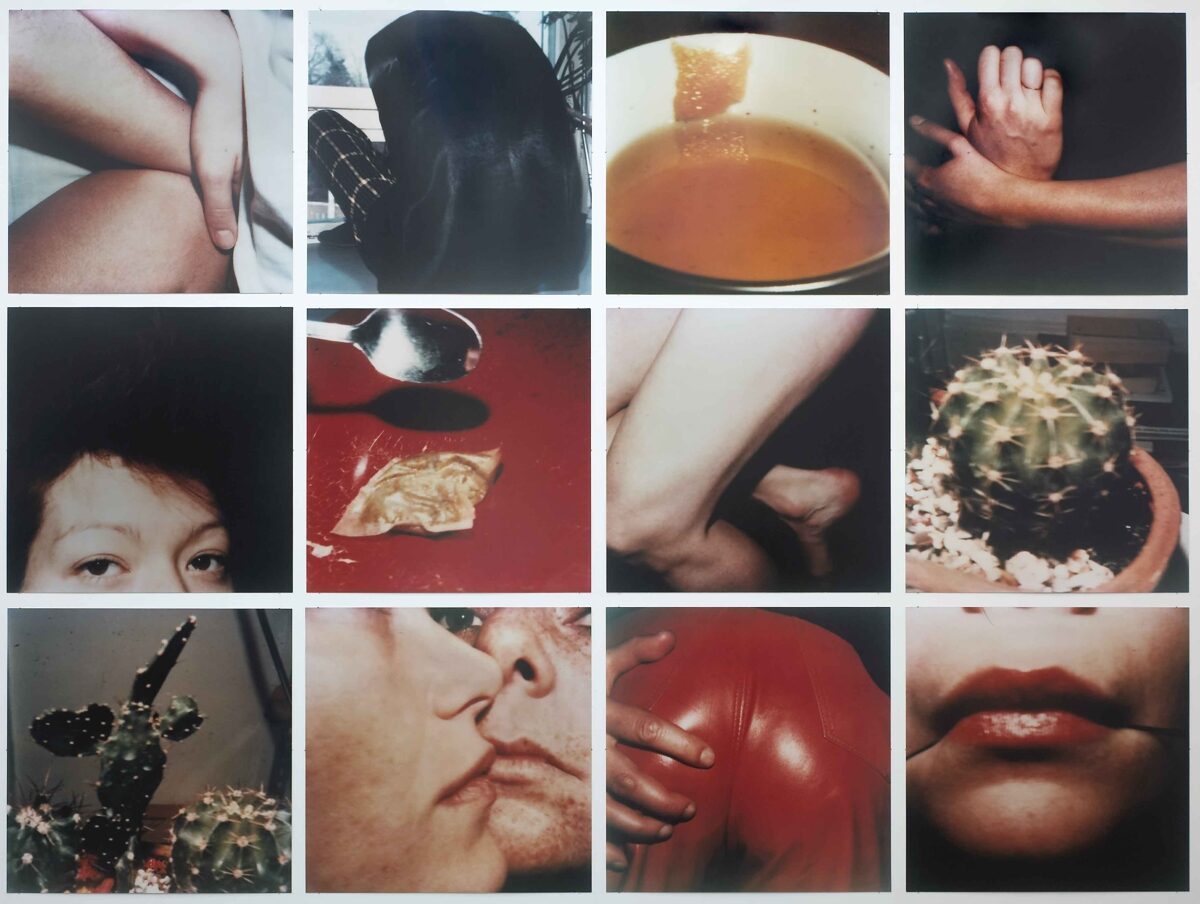

Die Art und Weise, wie Leutenegger nicht nur die eigene Figur zum Hauptakteur ihrer Kunst macht, sondern auch das Spiel mit den Geschlechterstereotypen lässt sich in der Tradition der feministischen Kunst verorten. Ihrer Arbeit fehlt aber sowohl die radikale Strenge der feministischen Künstlerinnen der ersten Generation als auch das Exhibitionistische und das Streben nach Tabubrüchen, wie wir es bei Künstlerinnen wie Sylvie Fleury (*1961), Tracey Emin (*1963) oder Pipilotti Rist (*1962) beobachten können, deren Schaffen ähnlich unermüdlich um die eigene Person kreist. Das Interesse der nachgeborenen Leutenegger gilt vielmehr den Eigenheiten und Erscheinungsweisen von Stereotypen als der Differenz zwischen den Geschlechtern. Leuteneggers Arbeit kann man in diesem Sinn als ausgesprochen persönlich bezeichnen, jedoch nicht als intim.

Yasmin Afschar

***

Using various media, Zilla Leutenegger (b. 1968) creates her very own work universe around the figure of “Zilla”, the artist’s alter ego and at the same time “an example to man”. She investigates the simple, but all the more existential questions of everyday life with childlike impartiality. In her drawings, video installations and sculptures she creates sceneries in which we recognise ourselves: “Zilla are many”, the critic Hans Rudolf Reust notes, and Leutenegger’s works accordingly tend to express exactly what we feel.

Memories of her own past and questions about female identity are recurring themes in Leutenegger’s work. Both realms found their way into the video installation “The Man in the Moon” from 2000, one of the artist’s best-known works which was acquired for the collection of the Aargauer Kunsthaus in 2002. We find ourselves in a black and white lunar landscape: a huge crater right in the middle, a golf cart-like vehicle in the background and, at the edge of the crater, the artist herself in a sporty outfit and hat. Stands there with legs apart, she rocks gently from her heels to her toes and pees like a man in a high arc into the crater, which inevitably elicits a chuckle from us. At the same time, she continuously whistles to herself the theme tune of “Once upon a Time in the West”. The scenery is illuminated by the glow of the terrestrial globe which, as the only coloured element, is added to the video sky through slide projection. A childhood memory underlies the origins of the work: as a little girl, Leutenegger imagined her father was living on the moon when he sent her a postcard from Texas showing the moon landing. Obviously, the video also has parodic elements. The fearless western hero, or the man who marks his territory by peeing, and the moon landing as one of the greatest milestones in twentieth-century history – Leutenegger confidently appropriates all these obviously masculine associations and exposes them with the kind of jaw-droppingly affectionate irony that is typical of her work. While the artist charmingly mimics male behaviour, the luminous “Mother Earth” high in the sky symbolises the feminine.

The way Leutenegger stylises herself as protagonist of her art and her play with gender stereotypes can be placed in the tradition of feminist art. But her work lacks both the radical rigor of first-generation feminist artists and the exhibitionism and urge to break taboos, which can observed in artists such as Sylvie Fleury (b.1961), Tracey Emin (b.1963) and Pipilotti Rist (b . 1962) whose work similarly revolves unremittingly around themselves. The later-born Leutenegger is interested more in the features and manifestations of stereotypes than in the difference between the sexes. In this sense, Leutenegger’s work may be described as eminently personal, but not intimate.

Yasmin Afschar

***

Zilla Leutenegger (*1968) crée, au moyen de différents médias, son propre univers d’œuvres autour de «Zilla», l’alter ego de l’artiste et en même temps un «exemple pour l’Homme». C’est avec une candeur enfantine qu’elle mène sa quête sur les questions simples mais ô combien existentielles du quotidien. Elle crée ainsi dans ses dessins, installations vidéo et sculptures des scènes dans lesquelles nous nous reconnaissons: «Beaucoup de gens sont Zilla», écrit le critique Hans Rudolf Reust, et de ce fait, les travaux de Leutenegger expriment très souvent ce que nous ressentons au plus profond de nous-même.

Tant les souvenirs de son propre passé que les questions relatives à l’identité féminine sont des thèmes récurrents dans l’œuvre de Leutenegger. Ces deux sphères sont reprises dans l’installation vidéo «Der Mann im Mond» de 2000, qui fait partie des travaux les plus connus de l’artiste et que l’Aargauer Kunsthaus a acquis en 2002 pour ses collections. Nous nous retrouvons dans un paysage lunaire noir et blanc: au milieu un immense cratère, à l’arrière-plan un véhicule ressemblant à une voiturette de golf et, au bord du cratère, l’artiste elle-même en tenue sportive avec une casquette. Elle se tient là debout les jambes écartées, bascule délicatement des talons vers la pointe des pieds et urine comme un homme dans le cratère en formant un grand arc, ce qui immanquablement nous fait sourire. Ce faisant, elle siffle sans discontinuer la mélodie «Il était une fois dans l’Ouest». La scène est éclairée par la lueur du globe terrestre, seul élément de couleur projeté à l’aide d’une diapo sur le ciel de la vidéo. Un souvenir d’enfance est à l’origine de ce travail: petite fille, Leutenegger s’imagine que son père vit sur la Lune, lorsqu’il lui envoie une carte postale du Texas représentant l’atterrissage sur la Lune. Manifestement, il y a aussi des éléments parodiques dans la vidéo: le héros de western sans peur, ou l’homme qui marque son domaine en urinant, ainsi que l’atterrissage sur la Lune, l’une des plus grandes conquêtes dans l’histoire du XXe siècle – Leutenegger s’approprie fièrement toutes ces associations aux connotations clairement masculines et les démasque avec une ironie incroyablement affectueuse, caractéristique de son travail. Tandis que l’artiste mime avec charme l’habitus masculin, la «Terre-Mère» lumineuse symbolise dans le ciel le féminin.

La manière dont Leutenegger fait non seulement de sa propre personne, mais aussi du jeu avec les stéréotypes sexués, l’acteur principal de son art permet de situer son œuvre dans la tradition de l’art féminin. Mais il manque à son travail aussi bien le rigorisme radical des artistes féministes de la première génération que le côté exhibitionniste et la chasse aux tabous, comme nous pouvons l’observer chez des artistes telles que Sylvie Fleury (*1961), Tracey Emin (*1963) ou Pipilotti Rist (*1962), dont les créations tournent tout autant inlassablement autour de leur propre personne. L’intérêt de Leutenegger, qui est née plus tard, porte davantage sur les particularités et le caractère des stéréotypes que sur la différence entre les sexes. De ce point de vue, on peut qualifier le travail de Leutenegger d’extrêmement personnel mais sans toutefois être intime.

Yasmin Afschar

***

Zilla Leutenegger (*1968) si avvale di diversi mezzi espressivi per creare il suo peculiare cosmo artistico, incentrato su “Zilla”, suo alter ego e nello stesso tempo figura “esemplare dell’essere umano”. Senza pregiudizi e con ingenua obiettività indaga i quesiti semplici ma profondamente esistenziali della vita quotidiana. Nei suoi disegni, nelle videoinstallazioni e nelle sculture crea degli scenari che ci rispecchiano: “Zilla sono tanti”, scrive il critico d’arte Hans Rudolf Reust, e infatti i suoi lavori ci parlano dal cuore.

I ricordi del proprio passato e l’interrogazione dell’identità femminile sono motivi ricorrenti nel lavoro di Leutenegger. Entrambe le sfere trovano un riscontro nella videoinstallazione Der Mann im Mond (L’uomo nella luna) del 2000, acquistato dall’Aargauer Kunsthaus nel 2002 e tra i lavori più noti dell’artista. Il video propone un paesaggio lunare in bianco e nero, con al centro un cratere, sullo sfondo un veicolo simile a un golf car e sull’orlo del cratere l’artista stessa, in tenuta sportiva, con un berretto in testa. A gambe divaricate, oscillando lievemente dai talloni alla punta dei piedi, è intenta a urinare nel cratere con un lungo getto ad arco, come fosse un uomo, fischiettando la melodia del film C’era una volta il West. La scena, che immancabilmente ci fa sorridere, è illuminata dal globo terrestre, l’unico elemento a colori proiettato tramite una diapositiva sulla videoproiezione, in corrispondenza del cielo. L’opera trae origine da un ricordo d’infanzia dell’artista: quando da bambina ricevette una cartolina da suo padre, inviata dal Texas, che riproduceva l’allunaggio, credette che egli vivesse sulla luna. Il video sottende però anche aspetti parodistici: l’eroe senza paura del film western, l’uomo che urinando segna il proprio territorio, o ancora lo sbarco sulla luna come una delle principali pietre miliari della storia del XX secolo. Leutenegger si appropria volutamente di queste associazioni a connotazione tipicamente maschile, smascherandole con l’ironia disarmante che distingue il suo lavoro. Mentre l’artista mima con fascino una consuetudine maschile, “madre Terra” che risplende dall’alto del cielo simboleggia la componente femminile.

Il modo in cui Leutenegger eleva a protagonista delle sue opere non solo la propria persona, ma anche il gioco con gli stereotipi di genere si inscrive nella tradizione dell’arte femminista. Il suo lavoro, tuttavia, elude il rigore radicale delle artiste femministe della prima generazione, così come l’aspetto esibizionista e la volontà di infrangere i tabù riscontrabili in artiste come Sylvie Fleury (*1961), Tracey Emin (*1963) e Pipilotti Rist (*1962), le cui opere ruotano anch’esse instancabilmente intorno alla propria persona. L’interesse di Leutenegger, nata qualche anno più tardi, è rivolto non tanto alla differenza tra i sessi, quanto piuttosto alle caratteristiche e alle espressioni degli stereotipi. In questo senso il lavoro di Leutenegger può essere considerato strettamente personale, ma non intimo.

Yasmin Afschar