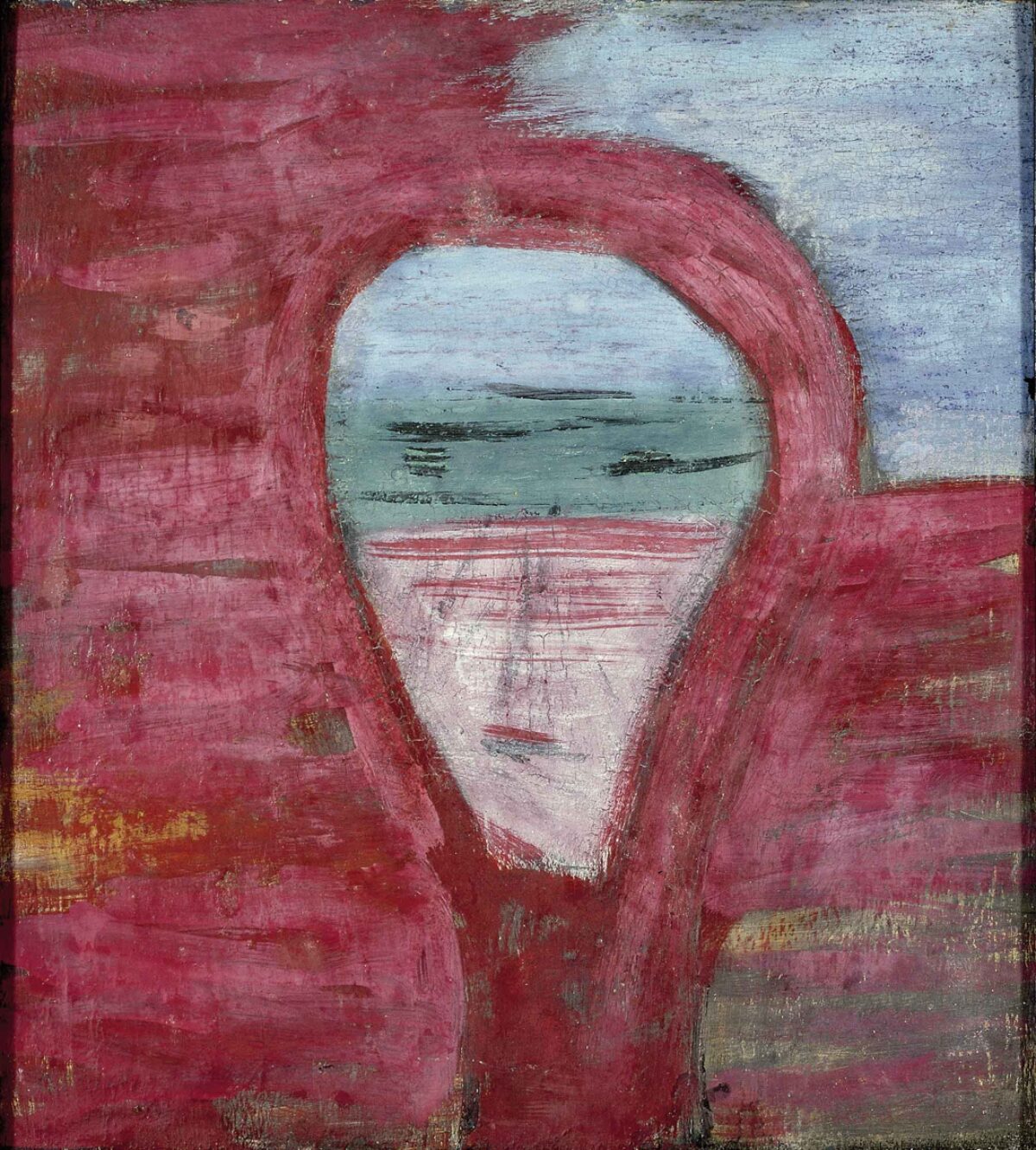

Öl auf Holz, 78 cm

English, french and italian version below

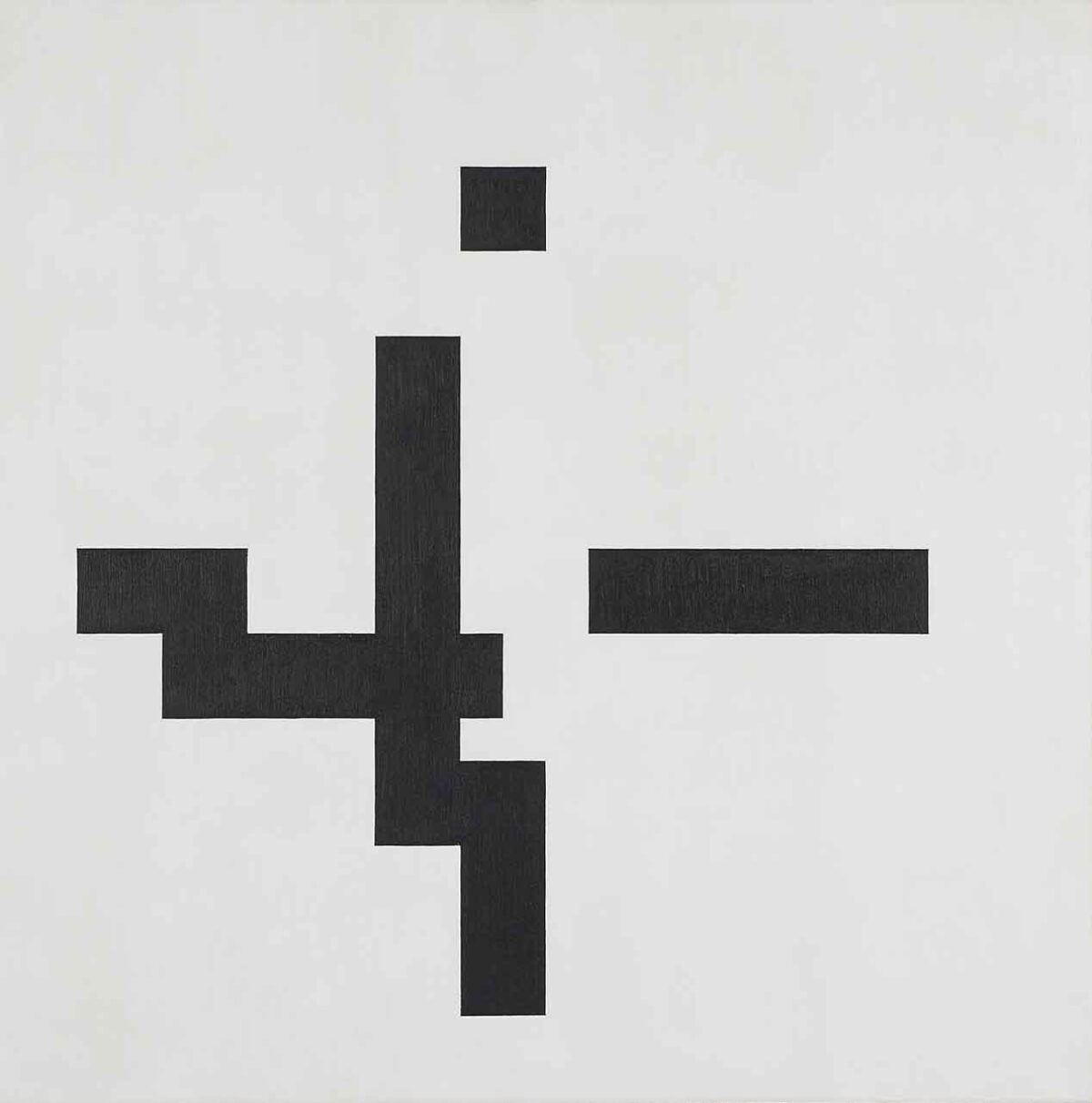

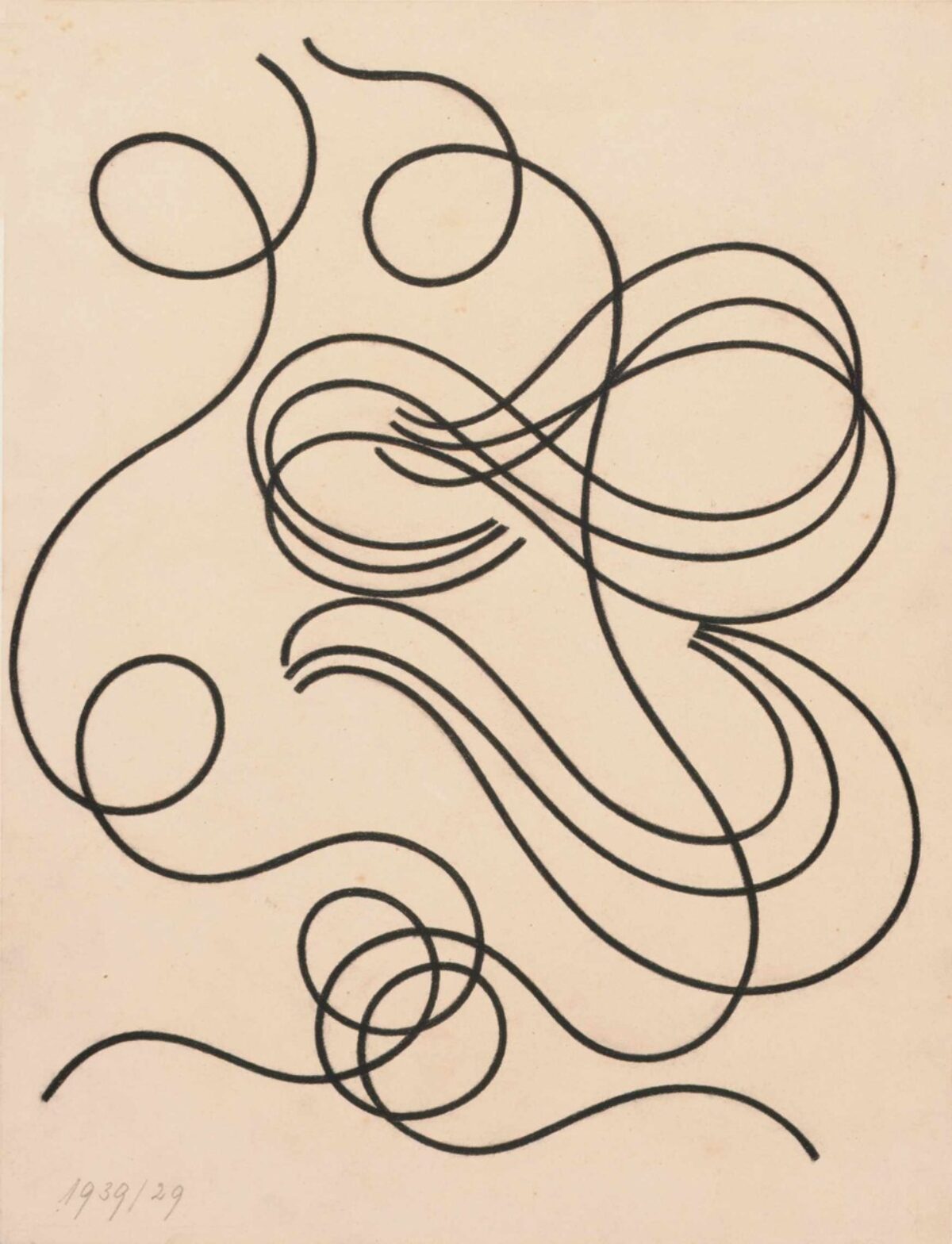

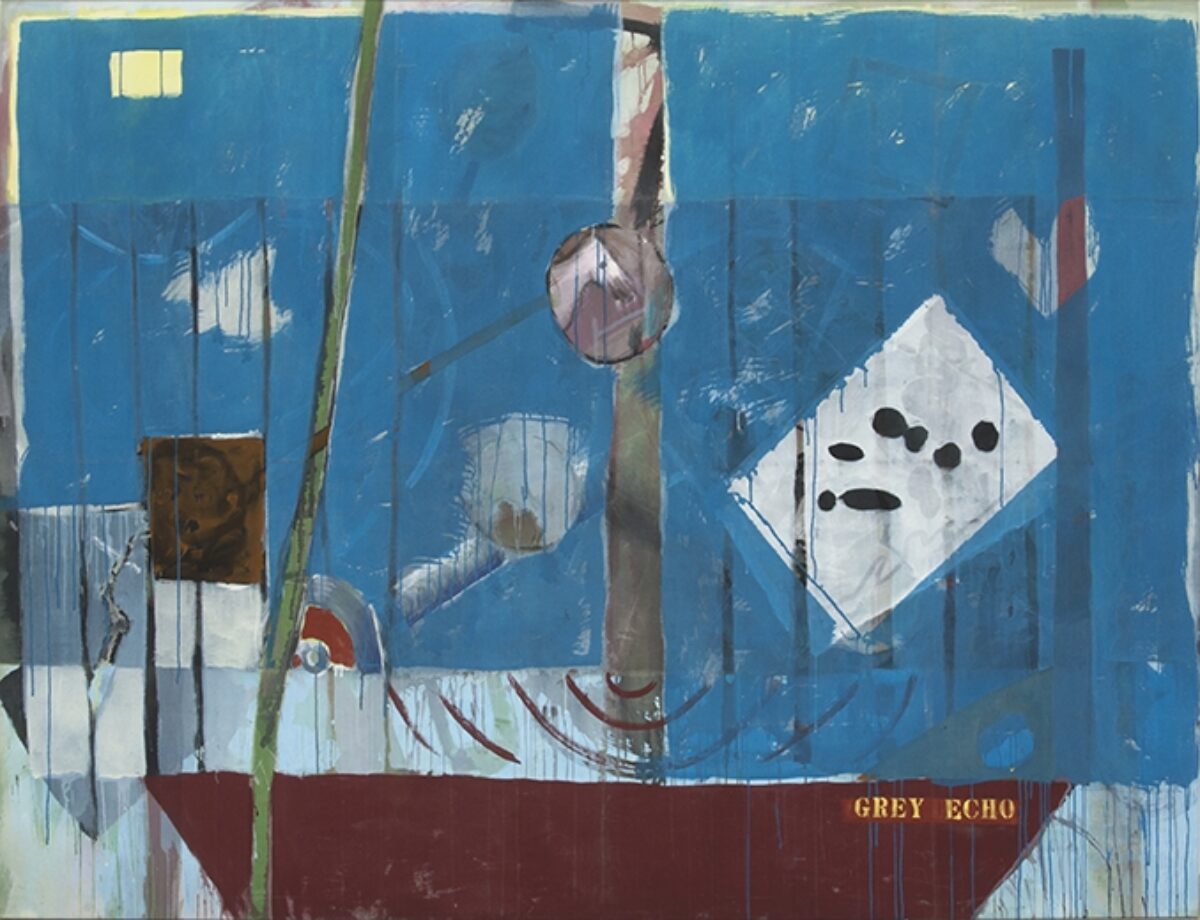

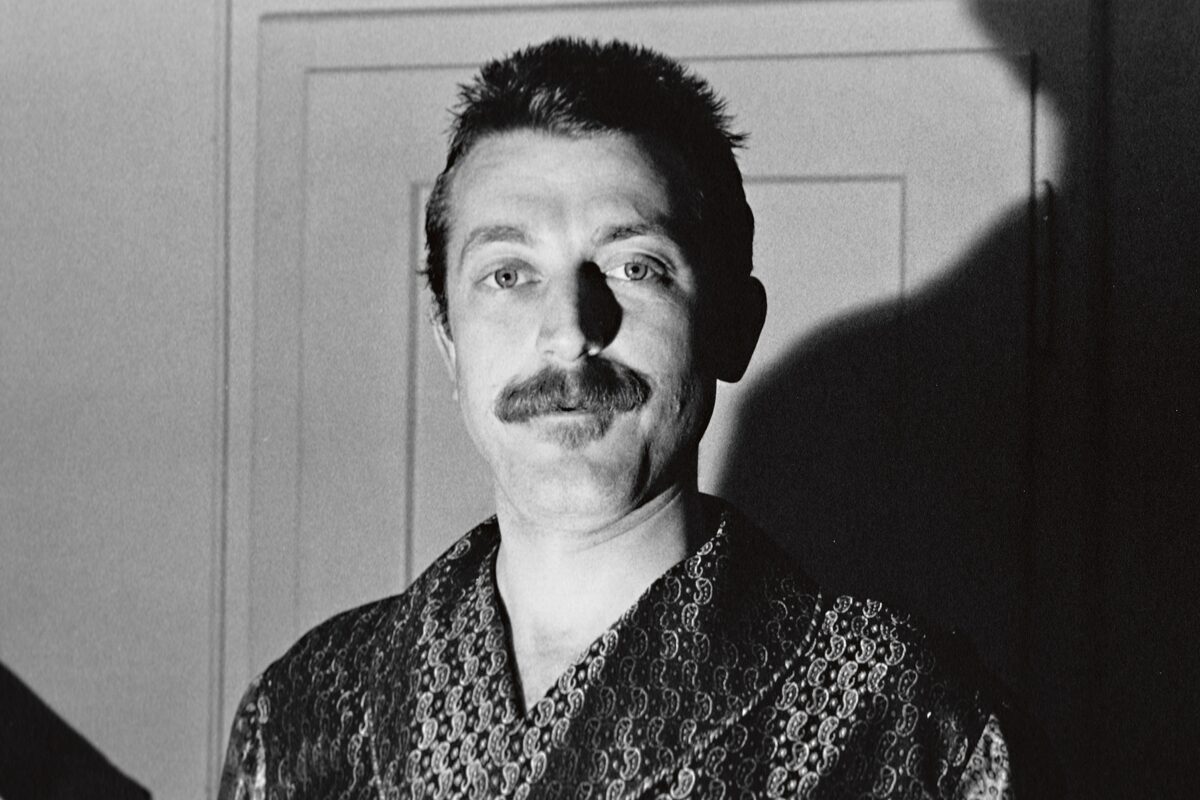

Fritz Glarner (1899–1972) zählt zu den namhaften europäischen Exponenten der geometrisch-abstrakten Kunst und zu ihren wichtigsten Vermittlern in den USA. Nach mehrjährigem Aufenthalt in Paris, wo er sich im Umfeld der Künstlergruppe „Abstraction-Création“ bewegt, seine Suche nach der Umsetzung des Raums in die Fläche aber noch losgelöst von der Avantgarde betreibt, übersiedelt er 1936 nach New York. Dort trifft er 1941 Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) wieder und formuliert im engen, freundschaftlichen Austausch mit dem Begründer des Neoplastizismus seine eigene, neuartige Antwort auf das Raum-Flächen-Problem. Von Mondrian übernimmt er die orthogonale Bildstruktur und die Beschränkung auf Rot, Gelb und Blau. Dieses Schema erweitert er jedoch wesentlich, indem er das Liniengerüst zusehends aufbricht und die Farbfelder unvermittelt aufeinanderprallen lässt. Dem reinen Weiss und den Primärfarben fügt er dabei feinste Gradierungen von Grau hinzu, die den Eindruck einer Tiefenstaffelung erwecken. Zudem treten zuweilen beim letzten Schritt der meist dreistufigen Teilung der Grundfläche Schrägen an die Stelle des rechtwinkligen Schnitts. So ergeben sich interagierende Keilformen, durch die das flächengebundene System auf rein optischem Weg eine Dynamisierung erfährt.

Für diese Art der rhythmischen Durchgestaltung der Bildfläche benutzt Glarner fortan die Bezeichnung „Relational Painting“. 1944 beginnt er, parallel zur Arbeit an rechteckigen Werken, das Prinzip auf Kreisformate, die Tondi, anzuwenden. In dieser Werkgruppe, die einer eigenen Zählweise folgt, behält er Mittel und Methode bei, sieht sich an den Rändern jedoch mit einer neuen Aufgabe konfrontiert: der Vermittlung zwischen Gerade und Kreissegment. Im vorliegenden Werk aus dem Jahr 1954 lässt sich beobachten, wie die Felder direkt in die Rundung übergehen. Dies entspricht der anfänglichen Lösung, während die späteren Tondi umlaufende, farblich abgesetzte schmale Streifen aufweisen, die den Grundgedanken von Glarners Malerei – die Beziehung der Bildelemente zueinander in einem abgeschlossenen Ganzen – wieder klarer unterstreichen. „Relational Painting, Tondo No 31“ ist das letzte Rundbild, das noch ohne diese Eingrenzung auskommt. Analog zu einer auch von Mondrian praktizierten Methode ist es aber bereits auf einen etwas grösseren Holzträger montiert. So ergibt sich eine Abstufung, die anstelle eines Rahmens ebenfalls eine Aussenlinie markiert.

In Bezug auf die Binnenstruktur liefert „Tondo No 31“ ein besonders ausgewogenes Beispiel für Glarners Gliederung der Fläche. Das Achsenkreuz ist wie üblich asymmetrisch gebrochen; dennoch wirkt es sorgfältig zentriert und fungiert visuell als Drehpunkt des Bildes. Dieser Eindruck setzt sich fort in der Organisation der Viertelkreise, deren einzelne Felder nicht nur entlang des Kreisrings ohne Abschluss sind, sondern im Unterschied zu den rechteckigen Bildern auch davor auf kein Element auflaufen, das sich ihnen quer entgegenstellt. Die L-förmigen Rhythmen können sich so ungehindert entwickeln, akzentuiert durch die Felder in Primärfarben, die mit ihrer planvollen Verteilung ebenfalls zur Ausbalancierung des Rundbildes beitragen. Selbst die Art des Farbauftrags scheint ausgeglichen, denn auf die sorgsam geglätteten Vertikalen antworten die Horizontalen mit einer Struktur, die den Pinselstrich lichtbrechend einsetzt. Für eine zweifelsfreie Ausrichtung sorgt schliesslich die frontseitig unten rechts im roten Feld platzierte Signatur. Für geometrisch-abstrakt arbeitende Künstler ist diese Form der Bezeichnung eher ungewöhnlich. Margit Staber zufolge, die 1976 die erste umfassende Werkmonografie verfasste, hat Glarner sie auf Wunsch seines Galeristen Louis Carré (1897–1977) aber öfter so angebracht.

Astrid Näff, 2018

***

Fritz Glarner (1899–1972) is one of the renowned European protagonists of geometric abstraction and one of its most influential practitioners in the USA. After spending several years in Paris, where he was close to the Abstraction-Création group of artists yet continued to experiment with ways of translating space into surface independent of the avant-garde, he moved to New York in 1936. There, he met Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) again in 1941 and, in a close and amicable exchange with the founder of Neo-Plasticism, developed his own, novel response to the problem of space and surface. He adopted Mondrian’s orthogonal pictorial structure and use of only red, yellow and blue, but significantly expanded this model by increasingly breaking up the structure of lines and causing colour fields to abruptly collide. He added the finest shades of grey to pure white and the primary colours, thereby creating the impression of a layering of depth. In the last of his usually three steps of subdividing the surface, moreover, oblique lines sometimes take the place of right-angle lines. This results in interacting wedge shapes which cause the surface-based system to be dynamized in a purely optical way.

Glarner from then on used the term “Relational Painting” to refer to this type of rhythmic all-over configuration of the pictorial surface. In 1944, while working on rectangular paintings, he began to apply the principle to circular formats, the tondi. In this group of works, which follow a distinct way of counting, he retained his means and method, but found himself confronted with a new task at the edges: reconciling straight line and arc. In this work from 1954 we can see the fields merge directly into the curve. This is consistent with the initial solution, whereas the later tondi feature circumferential, narrow strips of contrasting colour, which again underscore more clearly the basic idea of Glarner’s painting: the relationship of the pictorial elements to one another in a self-contained whole. “Relational Painting, Tondo No 31” is the last circular painting to still lack this “border”. Yet similar to a method also practiced by Mondrian, it is already mounted on a somewhat larger wooden support. This results in a gradation which similarly marks an outer line in place of a frame.

With regard to the internal structure, “Tondo No 31” offers a particularly balanced example of Glarner’s subdivision of the surface. As usual, the axis system is fractured asymmetrically; still, it appears carefully centred and visually acts as the fulcrum of the painting. This impression is reinforced by the organisation of the quadrants whose individual fields not only lack a border along the circular ring, but, even before it, do not collide with any element set perpendicularly against them like in the rectangular pictures. The L-shaped rhythms can thus develop unhindered, accentuated by the fields in primary colours whose systematic arrangement also helps balance the circular painting. Even the way the paint is applied seems balanced, as the horizontals respond to the carefully smoothed verticals with a structure using the brushstroke to refract light. Finally, an unequivocal orientation is ensured by the signature placed on the front in the red field on the bottom right. This type of inscription is rather unusual for artists practicing geometric abstraction. Yet according to Margit Staber, author of the first comprehensive monograph on the artist’s works in 1976, Glarner applied it more often in this way at the request of his gallerist, Louis Carré (1897–1977).

Astrid Näff, 2018

***

Fritz Glarner (1899–1972) fait partie des éminents représentants européens de l’abstraction géométrique et de ses principaux relais aux Etats-Unis. Après avoir passé plusieurs années à Paris où il fréquentait le groupe d’artistes «Abstraction-Création», recherchant une façon de transposer l’espace sur une surface, mais encore sans liens avec l’Avant-garde, il émigre à New York en 1936. C’est là qu’il retrouve Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) en 1941 et formule, au cours d’échanges étroits et amicaux avec le fondateur du néoplasticisme, sa propre réponse novatrice au problème espace-surface. Il reprend de Mondrian la structure orthogonale de l’image et la restriction au rouge, jaune et bleu. Cependant, il élargit substantiellement ce schéma en cassant de plus en plus la structure de lignes et en faisant s’affronter soudainement les champs de couleur. Au blanc pur et aux couleurs primaires il ajoute de très fines nuances de gris qui donnent l’impression d’une profondeur graduée. De plus, lors de la dernière étape de la partition, en général en trois plans, de la surface de base, des obliques se substituent à l’orthogonalité. Il en résulte des formes cunéiformes qui interagissent, grâce auxquelles le système lié à la surface disponible connaît une dynamisation par un pur biais optique.

Pour ce type de conception rythmique du tableau, Glarner utilise dorénavant l’appellation «Relational Painting». En 1944 il commence, parallèlement à son travail sur des tableaux rectangulaires, à appliquer le principe sur des cercles, les tondi. Dans cet ensemble d’œuvres, qui suit sa propre numérotation, il conserve les moyens et la méthode, mais se voit confronter à un nouveau défi: la transition entre le linéaire et le segment de cercle. Dans le présent tableau datant de 1954, on peut observer comment les champs se fondent dans l’arrondi. Cela correspond à la solution initiale, tandis que les tondi ultérieurs présentent tout autour de fines rayures de couleur contrastée, qui illustrent encore plus clairement l’idée fondamentale de la peinture de Glarner: la relation des éléments picturaux entre eux dans un tout fermé. «Relational Painting, Tondo No 31» est le dernier tondo qui se passe encore de cette délimitation. En analogie avec une méthode également pratiquée par Mondrian, il est cependant déjà monté sur un support en bois un peu plus grand. Il en résulte un dégradé qui marque aussi une ligne extérieure faisant fonction de cadre.

Concernant la structure intérieure, «Tondo No 31» livre un exemple particulièrement équilibré de la façon dont Glarner structure la surface. Comme d’habitude, la croix des axes est cassée de manière asymétrique; elle paraît pourtant minutieusement centrée et, visuellement, tient lieu de centre de rotation de l’image. Cette impression se poursuit dans l’organisation des quarts de cercle, dont les champs, non seulement, n’ont pas de terminaison le long de l’anneau du cercle mais ne rencontrent pas non plus auparavant d’élément faisant obstacle, contrairement aux tableaux rectangulaires. Les rythmes en forme de L peuvent ainsi se développer sans encombre, fait accentué par les champs aux couleurs primaires qui, de par leur répartition planifiée avec soins, contribuent également à l’harmonie du tondo. Même la façon dont la peinture est appliquée paraît équilibrée, car aux verticales soigneusement lissées répondent les horizontales avec une structure dont le recours au coup de pinceau produit un effet réfractaire. Au final, la signature placée sur le devant dans un champ rouge en bas à droite indique sans l’ombre d’un doute la bonne orientation. Cette forme de désignation est plutôt inhabituelle pour les artistes pratiquant l’abstraction géométrique. Selon Margit Staber, qui a signé en 1976 la première monographie complète des œuvres de Glarner, celui-ci l’a pourtant souvent fait à la demande de son galeriste Louis Carré (1897–1977).

Astrid Näff, 2018

***

Fritz Glarner (1899-1972) è un noto esponente europeo dell’astrazione geometrica e tra i principali divulgatori di questa corrente artistica negli Stati Uniti. Dopo un soggiorno pluriennale a Parigi – dove fa parte del gruppo “Abstraction-Création” e in autonomia rispetto alle Avanguardie cerca di trasporre lo spazio sulla superficie a due dimensioni – nel 1936 si trasferisce a New York. Nel 1941 ritrova Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) e attraverso uno scambio intenso e amichevole con il fondatore del Neoplasticismo matura la sua originale e innovativa risposta al problema dello spazio sulla superficie piana. Da Mondrian riprende l’impianto compositivo ortogonale e la limitazione cromatica ai colori primari rosso, giallo e blu. Glarner sviluppa però notevolmente queste premesse, allentando man mano l’impalcatura lineare e lasciando che i riquadri di colore siano a contatto diretto. Al bianco e ai colori primari aggiunge una delicata gamma di grigi, che genera l’impressione di piani scaglionati in profondità. Nell’ultima fase di suddivisione della superficie – solitamente tripartita – l’angolo retto viene talora sostituito da linee oblique. Si crea così un’interazione di riquadri cuneiformi, che sul piano ottico conferisce alla composizione bidimensionale un marcato effetto dinamico.

Per designare questa organizzazione ritmica della superficie, Glarner utilizza d’ora in poi la denominazione Relational Painting. Nel 1944, parallelamente al lavoro con i formati rettangolari, inizia ad applicare il suo principio operativo a tele circolari. In questo gruppo dei Tondi, numerati in modo autonomo rispetto agli altri lavori, Glarner mantiene gli stessi mezzi e metodi, ma lungo i margini della tela si trova confrontato con una nuova problematica: la mediazione tra la linea diritta e il segmento di cerchio. Nell’opera in esame, realizzata nel 1954, il passaggio dai riquadri ortogonali alla curvatura della tela è diretto. Rispetto a questa soluzione iniziale, i Tondi successivi presentano sottili tratti perimetrali, cromaticamente distinti, che pongono maggiormente in risalto il concetto di fondo della pittura di Glarner, ossia la relazione reciproca tra gli elementi d’immagine all’interno di un tutt’uno in sé concluso. Relational Painting, Tondo No 31 è l’ultima tela circolare risolta senza questi segmenti perimetrali. In analogia a un metodo praticato anche da Mondrian, la tela è però montata su un supporto ligneo leggermente più grande, in modo da ottenere una differenziazione che, al posto di una cornice, definisce una linea di confine.

Per quanto riguarda la struttura interna, Relational Painting, Tondo No 31 rappresenta un esempio particolarmente equilibrato dell’organizzazione formale che caratterizza la pittura di Glarner. L’incrocio degli assi mediani è asimmetrico, come sempre nei Tondi, ma ciononostante appare accuratamente centrato e funge da perno ottico del quadro. Lo stesso effetto si estende all’articolazione dei quarti di cerchio, i cui singoli riquadri sono privi non solo di linee lungo il margine circolare della tela, ma, a differenza dei lavori di formato rettangolare, anche di un elemento perpendicolare, contrapposto a T. I ritmi a forma di L si sviluppano pertanto in modo libero, accentuati dalle campiture nei colori primari che in virtù della loro distribuzione ponderata contribuiscono al bilanciamento del tondo. Perfino l’applicazione del colore sembra equilibrata, considerando che alle pennellate orientate in senso verticale, attentamente levigate, rispondono quelle orientate in orizzontale, più strutturate. L’orientamento inequivocabile dell’opera è attestato dalla firma, apposta al recto in basso a destra, all’interno del riquadro rosso. Nell’ambito dell’astrazione geometrica, una simile iscrizione è piuttosto insolita. Secondo Margit Staber, autrice della prima monografia dedicata all’artista, pubblicata nel 1976, l’iscrizione della firma in questi termini sarebbe riconducibile a una richiesta del suo gallerista Louis Carré (1897-1977).

Astrid Näff, 2018