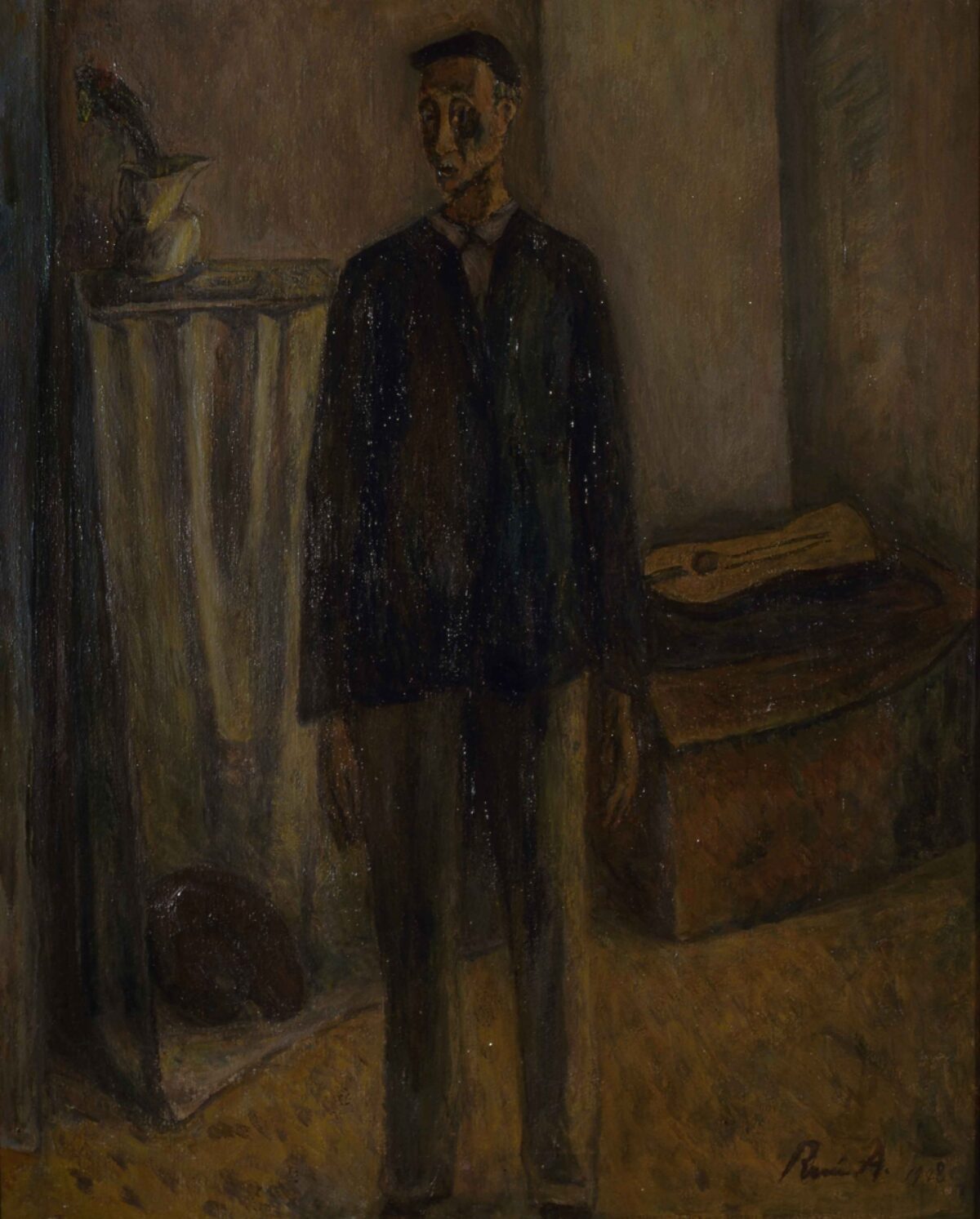

Öl auf Leinwand, 90 x 70 cm

English, french and italian version below

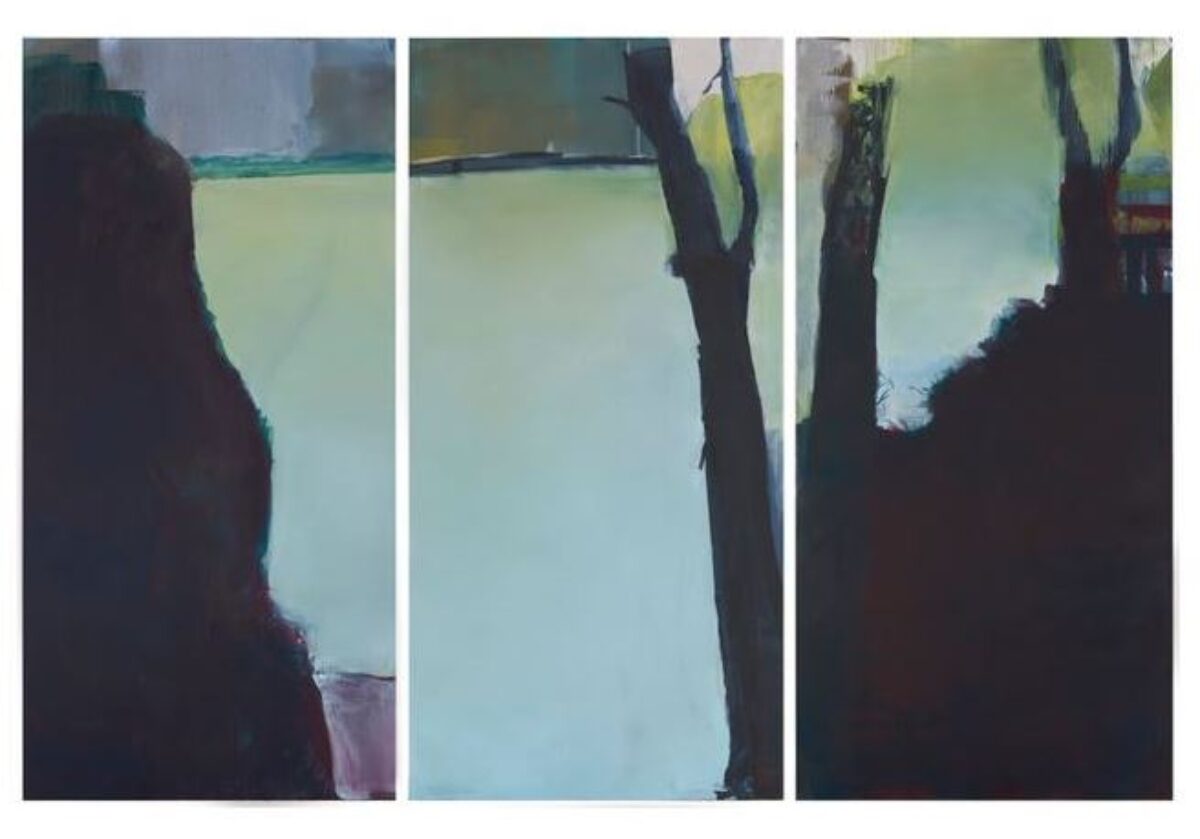

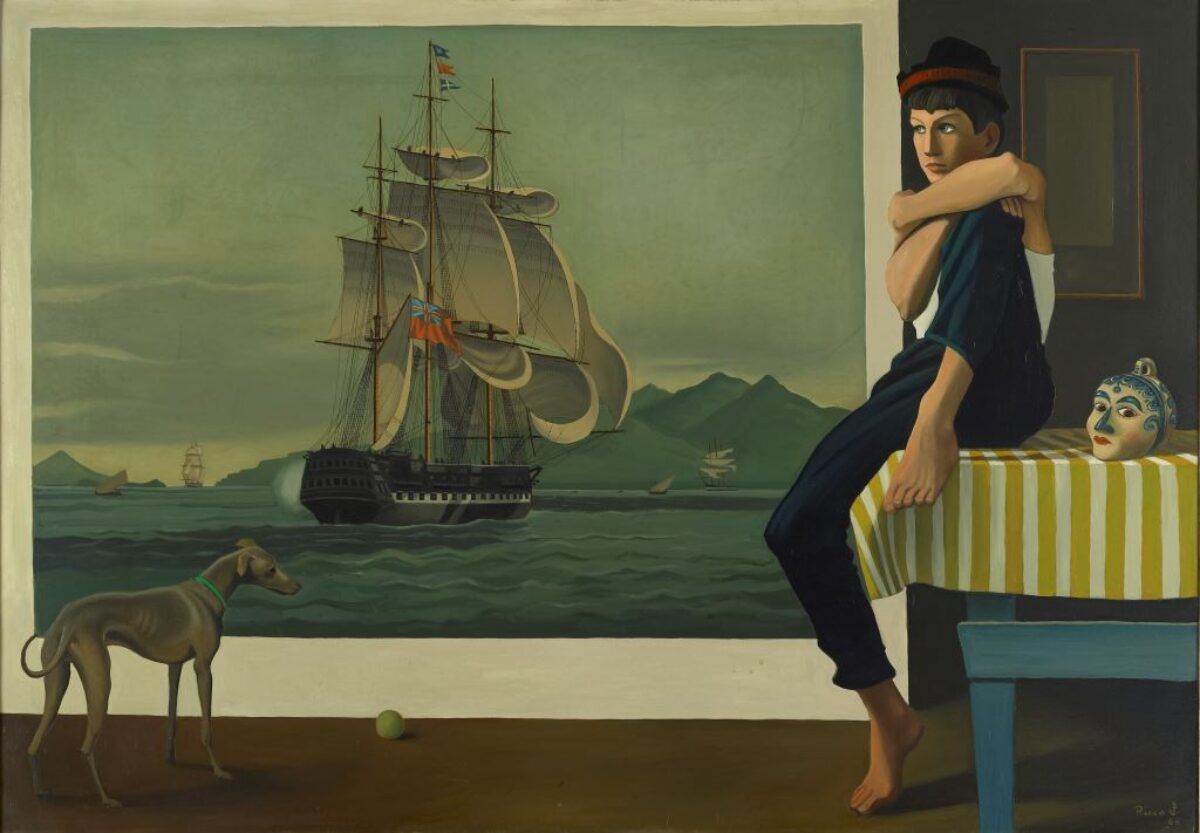

Die aufs Jahr 1903 datierten Landschaftsbilder „Mattina d’estate (Sommermorgen)“ und „Sera d’autunno (Herbstabend)“ werden in den Sammlungspräsentationen des Aargauer Kunsthauses oft als jahreszeitliches Stimmungspaar gezeigt. Auf beiden Gemälden blicken wir vom Tal her einen Flussstrom hinauf, über Wiesen, Buschlandschaften und darin eingebettete Häuser – hoch, zu einer den Horizont bezeichnenden Bergkette. In der sommerlichen Darstellung scheinen wir uns als Betrachtende inmitten einer Blumenwiese zu befinden. Am linken Bildrand tauchen die sonnenbestrahlten Häuserfronten eines Dorfs auf. Im Herbstbild „Sera d’autunno “ liegt der Betrachterstandpunkt etwas höher und weiter weg. Ein längeres Stück des Flusslaufs wird sichtbar und die entfernten Häuser erscheinen in der braun-violetten Heide lediglich als weisse Tupfer.

Giovanni Giacometti (1868–1939) schildert hier einen Abschnitt des dreissig Kilometer langen Val Bregaglias, das von der Oberengadiner Seenplatte, sprich von Maloja, bis hinunter ins italienische Grenzdorf Castasegna führt. Das angedeutete Dorf auf den Bildern lässt sich als Giacomettis Heimatdorf Stampa verifizieren. In seiner Malerei spiegelt sich die ungebrochene Verbundenheit zu diesem wildromantischen Tal wieder, das von dem Fluss Maira durchströmt und von spitzen Bergen gesäumt wird. Abgesehen von seinen frühen Studienjahren in München und Paris lebt und arbeitet Giacometti zeitlebens im Bergell und Oberengadin. Im Winter malt er das Leben im verschatteten Tal, im Herbst und Sommer die von Licht und Vegetation bunt erleuchteten Szenerien auf den Heiden und in den Stuben der Talbewohner*innen. Giovanni Giacometti trägt durch sein Einbringen des Kolorismus – eine Generation nach Ferdinand Hodler und Giovanni Segantini – entscheidend zum Aufbruch der Schweizer Moderne bei. Die Intensivierung von Farbe und Licht durchdringen sein gesamtes Werk, wobei er sich verschiedener stilistischer Mittel bedient. Am Anfang steht sein Interesse an der französischen Plenair-Malerei. Dieses wird während seines Studiums in München mitunter durch den Besuch der internationalen Kunstausstellung im Münchner Glaspalast 1888 geweckt. 1888 bis 1891 besucht er die Académie Julian in Paris und lebt in einer Atelier- und Wohngemeinschaft mit dem gleichaltrigen Solothurner Cuno Amiet, den er in seinem Münchner Studium kennengelernt hat. Die Sommermonate verbringen die Freunde in Stampa und Solothurn. 1891 reist Amiet in die bretonische Künstlerkolonie in Pont-Aven, wo er im Kreise der Gauguin-Nachfolger ein lehrreiches Jahr verbringt. Giacometti hingegen reist zurück in die Schweiz, wo er in eine künstlerische Krise stürzt. Sein Vorhaben, sich zwei Jahre später in Rom als selbständiger Künstler zu behaupten, scheitert. Wenngleich kaum Bilder aus der Italienzeit geblieben sind, so ist es dennoch das südliche Licht, welches von da an zu einer Aufhellung seiner Farbpalette führt. Den Ausweg aus der Krise bringt 1894 die Begegnung mit dem in Savognin ansässigen Italiener Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899). Giacometti eignet sich dessen Errungenschaft, die divisionistische Malerei an, bei welcher Komplementärfarben in feinen Strichen nebeneinandergesetzt werden. Segantinis Tod trifft Giacometti hart, befreit ihn aber auch von dessen dominantem Vorbild und weist ihm den Weg zu einer eigenständigeren Gestaltungsweise. Hierbei kehrt er sich von dem dichten, gewebartigen Divisionismus ab, hin zu einer freieren, flockigeren Tupftechnik – dem Pointilismus. Doch auch dieser Technik bleibt er nur eine kurze Phase verbunden, während sich ein expressiverer Pinselduktus und eine kühne Koloristik zu den eigentlichen Merkmalen seiner Malerei entwickeln.

Die beiden Landschaftsbilder fallen sichtbar in eine Zeit des Übergangs, der Suche nach dem eigenen Stil: Während in „Sera d’autunno“ das divisionistische Erbe in allen Naturformen und Texturen nachklingt, flackert der gestrichelte Pinselduktus in „Mattina d’estate (Sommermorgen)“ nur partiell als Flimmern des gleissenden Sommerlichts auf Gräsern und Bäumen auf. Viele Elemente werden dagegen flächig, fast scherenschnittgleich behandelt. Über die Wahl unterschiedlicher Techniken gelingt es dem Maler, zu spiegeln, wie je nach Tages- und Jahreszeit ein und dieselbe Landschaft als lieblich-weich oder aber als konturiert-markant aufscheint.

Julia Schallberger

***

In presentations of the collection of the Aargauer Kunsthaus, the two landscapes “Summer Morning” and “Autumn Evening” (both dated 1903) are frequently shown as a pair of paintings conveying the atmosphere of the season. In both works we look from the valley up a stream, across fields, scrubland with houses embedded in it and, at the top, a mountain ridge marking the horizon. In the painting of summer, we as viewers seem to find ourselves in the middle of a flowering meadow. The sunlit house fronts of a village appear on the left side of the image. In the autumn painting the viewer’s vantage point is slightly higher and further away. A longer stretch of the river is visible and the distant houses appear as mere white specks in the brown and purple heather.

Giovanni Giacometti (1868–1939) depicts a section of the thirty-kilometre-long Val Bregaglia here, which runs from the Upper Engadine lake plateau – that is, from Maloja – all the way down to the Italian border village of Castasegna. The village hinted at in the paintings may be identified as Giacometti’s home town of Stampa. His painterly work reflects his unwavering attachment to this wild and romantic valley with the river Maira flowing through it and the pointy mountains lining it. Except for his early years as a student in Munich and Paris, Giacometti lives and works all his life in the Val Bregaglia and the Upper Engadin. In the wintertime he paints life in the shaded valley and in the autumn and summer he captures the scenery, colourfully illuminated by sunlight and vegetation, on the heath and in the parlours of the valley dwellers. Giovanni Giacometti’s introduction of colourism – a generation after Ferdinand Hodler and Giovanni Segantini – contributes crucially to the emergence of Swiss modernism. The now more intense colour and light suffuse his entire work, irrespective of the various stylistic means he employs.

At the beginning of his career, his interest in French plein-air painting is aroused during his studies in Munich when he visits the International Art Exhibition in Munich’s Glass Palace in 1888. From 1888 to 1891 he attends the Académie Julian in Paris and lives in a studio- and flat-sharing community with the Solothurn-born Cuno Amiet whom he has met while studying in Munich. The friends spend the summer months in Stampa and Solothurn. In 1891 Amiet travels to the Breton artists’ colony in Pont-Aven, where he spends an instructive year among followers of Gauguin. Giacometti, on the other hand, returns to Switzerland where he slides into an artistic crisis. His plan to establish himself as an independent artist in Rome two years later fails. Even though hardly any paintings from the Italian period survive, it is the southern light that subsequently leads to a brightening of his colour palette. The way out of the crisis comes in 1894 when he meets the Italian painter Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) who lives in the Grisons town of Savognin. Giacometti adopts his Divisionist style which involves separating colours in individual dots or strokes. Segantini’s death hits Giacometti hard, but it also frees him from his dominant example and points him towards a more independent style. He turns away from dense, mesh-like Divisionism and towards the looser, fluffier stippling technique of Pointillism. But he also uses this technique only for a short period, while more expressive brushwork and bold colouring emerge as the real characteristics of his painting.

The two landscapes visibly fall in a transitional period when he is searching for his own unique style: in “Autumn Evening”, echoes of the Divisionist legacy still linger in all of the natural forms and textures, whereas in “Summer Morning” the dashed brushwork flashes only partially as the flickering of blazing summer light on grasses and trees. Many elements, by contrast, are rendered two-dimensionally, almost silhouette-like. By choosing different techniques, the painter manages to show how, depending on the time of day and season, one and the same landscape appears smooth and soft or, alternatively, contoured and clear-cut.

Julia Schallberger

***

Datés de 1903, les tableaux de paysage «Mattina d’estate» (matin d’été) et «Sera d’autunno» sont souvent montrés dans les présentations des collections de l’Aargauer Kunsthaus comme paire de tableaux saisonniers. Sur les deux toiles, nos yeux suivent, depuis la vallée, une rivière sillonnant prairies et paysages de broussailles, où sont nichées des maisons, jusqu’à une chaîne de montagnes marquant l’horizon. Dans celle représentant l’été, nous avons l’impression, en tant qu’observateurs, de nous trouver au milieu d’un pré fleuri. Sur le bord gauche du tableau apparaissent les façades ensoleillées des maisons d’un village. Pour le tableau automnal «Sera d’autunno», la perspective de l’observateur se situe un peu plus haut et plus loin. On distingue une portion plus longue du cours de la rivière et les maisons éloignées apparaissent seulement comme de petites touches blanches dans la lande brun violet.

Giovanni Giacometti (1868–1939) décrit ici un tronçon du val Bregaglia long de trente kilomètres, qui descend de la région des lacs de la Haute-Engadine, c’est-à-dire de Maloja, jusqu’au village de Castasegna à la frontière italienne. Le village esquissé sur les tableaux est, comme on peut le vérifier, Stampa, le village natal de Giacometti dont la peinture reflète son attachement inébranlable à cette vallée au romantisme sauvage, traversée par la rivière Maira et bordée de hautes montagnes. Hormis ses premières années d’études à Munich et Paris, Giacometti vit et travaille sa vie durant dans le val de Bregaglia et en Haute-Engadine. En hiver, il peint la vie dans la vallée plongée dans l’ombre, à l’automne et en été des scènes, inondées de lumière et des couleurs chatoyantes de la végétation, sur la lande et dans les intérieurs des habitants de la vallée. En introduisant le colorisme, une génération après Ferdinand Hodler et Giovanni Segantini, Giovanni Giacometti apporte une contribution décisive à l’éclosion du mouvement moderne de la peinture suisse. L’intensification tant de la couleur que de la lumière irradie l’ensemble de son œuvre, tout en ayant recours à divers moyens stylistiques. Au commencement, il y a son intérêt pour la peinture de plein air française, intérêt suscité durant ses études à Munich notamment par la visite de l’exposition internationale d’art en 1888 au Palais des glaces de Munich. De 1888 à 1891, il suit les cours de l’Académie Julian à Paris où il partage le logement et l’atelier avec le Soleurois du même âge que lui, Cuno Amiet, dont il a fait la connaissance pendant ses études à Munich. Les deux amis passent les mois d’été à Stampa et Soleure. En 1891 Amiet part rejoindre la colonie d’artistes à Pont-Aven en Bretagne, où il passe une année très instructive au sein du cercle des successeurs de Gauguin. Giacometti, en revanche, rentre en Suisse où il sombre dans une crise artistique. Son intention de s’imposer deux ans plus tard comme artiste indépendant à Rome échoue. Même si très peu de tableaux de la période italienne nous sont parvenus, c’est pourtant la lumière méditerranéenne qui contribue dès lors à l’éclaircissement de sa palette de couleurs. Sa rencontre en 1894 avec l’Italien Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) habitant à Savognin lui permet de sortir de la crise. Giacometti s’approprie sa technique innovante, la peinture divisionniste consistant à juxtaposer des traits fins de couleurs complémentaires. La mort de Segantini est un choc pour Giacometti, qui le libère toutefois de son modèle et inspirateur dominant et lui ouvre la voie vers une création plus personnelle. Ce faisant, il s’éloigne du divisionnisme et de ses structures plus grossières semblables à un tissu, pour s’adonner à une technique par touches plus libre et plus floconneuse, le pointillisme. Mais même cette technique, il ne la pratiquera que durant une courte phase, tandis qu’un trait de pinceau plus expressif et une coloristique audacieuse deviennent les véritables marques distinctives de sa peinture.

Les deux tableaux de paysage tombent visiblement dans une période de transition à la recherche de son propre style: alors que dans «Sera d’autunno» l’héritage divisionniste est perceptible dans toutes les textures et formes se rapportant à la nature, le trait de pinceau pointillé dans «Mattina d’estate» n’émerge que partiellement en tant que scintillement de la lumière étincelante du soleil sur les herbes et les arbres. De nombreux éléments deviennent en revanche plats, un peu comme s’ils avaient été découpés aux ciseaux. En choisissant différentes techniques, le peintre réussit à exprimer comment, selon la saison et le moment de la journée, un seul et même paysage révèle une tendre douceur ou, au contraire, des contours saillants.

Julia Schallberger

***

I due paesaggi datati al 1903, intitolati “Mattina d’estate” e “Sera d’autunno”, sono spesso esposti nella collezione permanente dell’Aargauer Kunsthaus come duetto di atmosfere stagionali. Entrambi i dipinti presentano il corso di un fiume, visto da valle verso monte, costeggiato da prati, vegetazione arbustiva e qualche casa isolata, con una catena di montagne all’orizzonte. Il quadro estivo sembra situarci in mezzo a un prato fiorito; a sinistra si stagliano le facciate in pieno sole delle case di un villaggio. In “Sera d’autunno” il punto di vista è situato più in alto e a maggiore distanza; intravediamo un segmento più lungo del corso del fiume e le case disseminate nella landa marrone-viola sono meri punti bianchi.

In “Sera d’autunno”, Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1939) rappresenta uno scorcio della Val Bregaglia, lunga una trentina di chilometri, che dall’altopiano dei laghi dell’Alta Engadina, ossia da Maloja, si estende fino al villaggio di Castasegna, al confine con l’Italia. Il villaggio, appena evocato nei due quadri, può essere identificato con Stampa, il paese natale di Giacometti. Le sue opere tradiscono infatti un profondo legame con questa valle selvaggia e romantica, attraversata dal fiume Maira e costeggiata da alte vette. A prescindere dagli anni giovanili di studio a Monaco di Baviera e Parigi, Giacometti vive e lavora tutta la vita in Val Bregaglia e nell’Alta Engadina. In inverno dipinge la vita del fondovalle ombroso, in autunno e in estate le lande soleggiate e rigogliose e gli interni delle case dei valligiani. Con l’introduzione del colorismo – una generazione dopo Ferdinand Hodler e Giovanni Segantini – Giacometti dà un contributo decisivo alla svolta dell’arte moderna in Svizzera. L’esaltazione del colore e della luce, sviluppata con diversi mezzi stilistici, alimenta tutta la sua ricerca. L’esordio è improntato all’interesse per la pittura francese en plein air, scoperta in occasione della visita dell’Esposizione internazionale d’arte al Palazzo di vetro di Monaco di Baviera nel 1888. Dal 1888 al 1891 frequenta l’Académie Julian a Parigi e condivide l’atelier e l’alloggio con il coetaneo Cuno Amiet, di Soletta, conosciuto durante gli studi a Monaco di Baviera. I due amici trascorrono i mesi estivi rispettivamente a Stampa e a Soletta. Nel 1891 Amiet si reca in Bretagna, presso la colonia degli artisti di Pont-Aven, dove trascorre un anno intenso e fruttuoso nella cerchia dei seguaci di Gauguin. Giacometti, invece, rientra in Svizzera e cade in una profonda crisi artistica. Il proposito di affermarsi, due anni più tardi, come artista indipendente a Roma, fallisce. Anche se le opere del periodo italiano sono quasi tutte disperse, la luce meridionale ha indubbiamente innescato il cammino verso lo schiarimento della tavolozza. Il superamento della crisi avviene nel 1894, grazie all’incontro con l’artista italiano Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899), residente a Savognin. Giacometti fa propria la scoperta maturata da Segantini – la tecnica divisionista – nella quale i colori complementari vengono accostati in tratti sottili. La morte di Segantini colpisce duramente Giacometti, ma nel contempo lo libera dal modello dominante e lo guida verso la maturazione di un linguaggio più autonomo. Giacometti si allontana dalla densa tessitura della pittura divisionista a favore di una tecnica più libera e ariosa – il puntinismo – basata sulla scomposizione del colore in piccoli punti. Anche la pratica di questa tecnica, tuttavia, è solo temporanea e lascia progressivamente spazio a pennellate più espressive e a scelte cromatiche più audaci, che diventano gli stilemi distintivi della pittura di Giacometti.

“Mattina d’estate” e “Sera d’autunno” si inscrivono chiaramente in una fase di passaggio e di ricerca del proprio stile: se nella fattura pittorica e nelle forme naturali di “Sera d’autunno” è evidente il retaggio divisionista, le pennellate sottili e filamentose di “Mattina d’estate” rispecchiano solo parzialmente il riverbero dell’intensa luce estiva sull’erba e sugli alberi. Molti elementi appaiono appiattiti, come fossero ritagliati. Valendosi di tecniche diverse, Giacometti riesce cioè a esprimere la mutevolezza di uno stesso paesaggio secondo il momento della giornata e della stagione, raffigurandolo ora con tratti morbidi e sfumati, ora con contorni più marcati.

Julia Schallberger